Loud and Strong, First Women Dockworker on the West Coast.

December 2, 1942, San Francisco — August 23, 2020 age 77, Long Beach

Meet Sharon Ann Cotrell, a leader of social justice causes in Long Beach for over fifty years. I call her, “my friend, the historical figure.” We met in a Women’s Studies seminar taught by Sherna Gluck at California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) in 1991. The research goal was to expand the narrative of the “Second Wave” feminist movement to West Coast working class, poor, and minority women. Sharon chose to research American Indian women and explore her heritage as Métis with Little Shell Chippewa, Cherokee and perhaps runaway slaves. She conducted oral histories with local Indian women including Lillian Robles and Tongva women leaders. This research led her to become a Tongva tribal researcher assisting in their quest for national and state tribal recognition.

Sharon, born in San Francisco in 1942, spent her childhood on a dairy farm in the Lower Flathead Valley, Montana where she says that they produced a lot more manure than milk. As the oldest of four sisters, she helped her father in the barn and fields, and helped her mother with her sisters. She took pride in working like a son with her father. Farm life taught her physical strength, endurance, self-reliance and deep respect for nature. She thought her formal education in St. Ignatius on the Flathead Indian Reservation was inadequate.

In 1957, fifteen-year old Sharon was horrified by television images of the attacks on Black children attending Little Rock High School and other violent attacks on African Americans. She asked teachers and family around her how racism could still exist? How adults could behave so badly? And what had they done about it? She found their bewilderment shameful. The librarian at St. Ignatius High School ordered books on African American history and racism from the University of Montana library for her, igniting Sharon’s lifelong journey for knowledge and justice.

Sharon had a brilliant mind with an exacting memory for dates, places and events, a voracious appetite for reading, and an analytical intellect. Yet, completing a degree in Anthropology was a thirty-year journey, starting with Lewis and Clark University in Portland in the 1960s, then the University of Montana, and finally at CSULB in the early 1990s.

Following her family to Long Beach in 1964, Sharon rented an apartment in the central area to be part of the African American community. She joined many of her neighbors on civil rights and welfare rights issues. She was warmly included in War on Poverty activist Dale Clinton’s family. After racial tensions exploded in 1967 at Polytechnic High School, Sharon called a meeting at the Long Beach Community Improvement League hall, helped form an interracial group called FREE, and was their only paid staff for a while.

In 1974, Sharon, was still struggling to make a living as a waitress and finish college. Many of her customers made a good living on the docks at the Port of Long Beach. “A light went on.” She followed the men to the money. She was hired at SeaLand as the first women dockworker on the West Coast and became our feminist “historical figure.”

The Teamsters Union job unloading cargo ships was difficult and dangerous. She had no mentors–male workers were hostile, relegating her to the most physical jobs. She worried constantly about injury and sabotage. But she also noticed that the local Teamsters Union 692 was not addressing the workers’ needs under the Hoffa leadership of Jake Koenig, Gunner Hansen and their thugs. She became active in the union, studying the contract and effectively arguing appeals, she won the men over with her curiosity, tenacity, competence, and intelligence. She and Bilal Chaca were determined to institute democracy and promote the workers’ needs. They co-founded the local Teamsters for Democratic Union (TDU), joining the national movement. The unwelcome woman was elected shop steward! Others who attempted reform were badly beaten. She went into hiding for several months, living with friend, Barry Saks. He says, “She not only risked her life but gave an enormous amount of money to the TDU.” Eventually, a confrontation occurred in the dark at the Port. Sharon yelled at the thugs, “I am not stopping; you are just going to have to kill me.” She thought her bravery came from standing up to her father. She speculated that she survived because they just did not know how to beat up or kill a woman.

Sharon’s dedication to the TDU meant she worked days at SeaLand and through the night building the organization. She would be awake for days at a time, fueled partly by alcohol. Eventually, she overcame addictions to alcohol and cigarettes with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous, bolstered often by quoting AA wisdoms.

Sharon used her organizing skills like breathing. Her goal was building networks for social justice on almost every issue. She reached out to secular and religious groups such as the South Coast Interfaith Council, Central Shalom, and Black Lives Matter. Where did she get these skills? An early source was training by International Socialists. With each social justice group Sharon joined, she honed her organizing skills. She led and encouraged activists in all the tactics and strategies she practiced such as research, teach-ins, marches, demonstrations, lawsuits, fundraising, lobbying, and founding new organizations.

Sharon was a leader in Long Beach Area Citizen’s Involved (LBACI), a progressive organization that worked on issues such as police accountability and the establishment of the Citizen Police Complaint Commission. LBACHI helped change school board elections to increase diversity. As a result, Sharon ran several campaigns such as Alan Lowenthal’s first election to the Long Beach City Council in 1992. She also ran Tom Clark and Wally Edgerton’s campaigns because these Republicans were more liberal than the other candidates. Then they would be obligated to listen. She even cajoled Peace and Freedom party members to make campaign calls for Edgerton—that is how skillful she was.

Sharon was a founding member of The Long Beach Area Peace Network (LBAPN), a coalition of justice groups that grew out of the folding of the LBACI. When the Long Beach police overreacted and attacked the peaceful anarchist demonstration on Pine Avenue in 1999. Sharon led community outrage. Sharon arranged pro-bono ACLU legal counsel, organized support at trials, and led protests at the court house. The prosecutors pressured young people to plead guilty while they ignored police brutality.

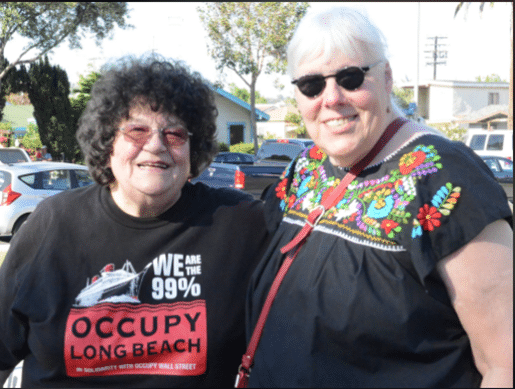

Starting in 2003, Sharon could be seen gathering contacts as part of the Second Street peace vigils against the Iraq war on Friday nights. In 2011, Sharon joined the Occupy Long Beach general assembly on the second night. Occupy Long Beach was inspired by Occupy New York—protesting economic injustice amid bank bailouts, encapsulated in the slogan, “We Are the 99%.”

She constrained her big and loud presence to mentor and collaborate with participants—young, old, anti-war, homeless, veterans, everyone drawn to the umbrella of economic justice. Sharon led the Occupy strategy to “Stop Foreclosures” with legal research, bank negotiations, neighborhood canvassing, sheriff confrontations, and massive food preparations for the occupiers.

Sharon’s far ranging work for social justice includes many other causes such as the May Day Coalition, campaigns for LGBTQ rights, East Yard Environmental Justice, sentencing reform, and Puvungna Coalition to save sacred land at CSULB. She founded People for Palestine Israeli Justice (PPIJ) with Dennis Kortheuer in 2014 when the Gaza War erupted. Amidst these accomplishments was a long-term struggle with depression, irregular sleep, and physical ailments. She called it “going down.” These episodes lasted for days or weeks or months. LBAPN founder Gene Ruyle recalls, “When she came back up, she accomplished three times as much as the rest of us.”

Upon her death, Congressman Alan Lowenthal remembered Sharon,

Family and friends gathered for a Zoom memorial. People recalled how she influenced them and changed their lives. Dee Hunt wrote, “She inspired me to enter a field dominated by men… my career path leading to Manager of Engineering Systems for a Fortune 100 company.” Activist Erin Foley said,

Dennis Rockway recalled,

Teresa Sanders remembered, “She seemed to approach her personal health problems with the same stamina she showed in her political activities…. Good job, Sharon, your part is done.” Her life could make a novel or best-selling memoir if only we had recorded her larger than life stories.

In memoriam, Sharon’s materials from her lifetime of justice work will be preserved at the Historical Society of Long Beach and the labor archives at California State University, Northridge.

Sharon often said,

By Karen S. Harper, Community Historian

Edited Julie Bartolotto, Project Director