This page provides more information on the Cambodian diaspora in the United States. The first section covers evacuees, the majority of whom arrived in the U.S. shortly after the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia in 1975. Next is the arrival of refugees between 1979 and 1990. This is followed by a short discussion of Cambodian American concerns for their homeland (see “Global Awareness and Cambodian Activism/Advocacy 1975-1979” for additional information). The page closes with a Press-Telegram special report on Chantara Nop’s first return home to Cambodia just as the country was re-opening in 1989.

Cambodians are a relatively recent immigrant group in America’s history, and their story is very different from immigrants who came to this country before them. While most new immigrants can count on well-established communities to provide both emotional and economic support while adjusting to American life, Cambodians had no such luxury. Only a handful of Cambodians lived in the U.S. prior to 1975, and although they immediately extended help to those arriving in the early days, the essential networks and bridges to mainstream American life, jobs, and language had to be created.

Additional Resources

✧ The Cambodian Diaspora Community Building in America

✧ Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement

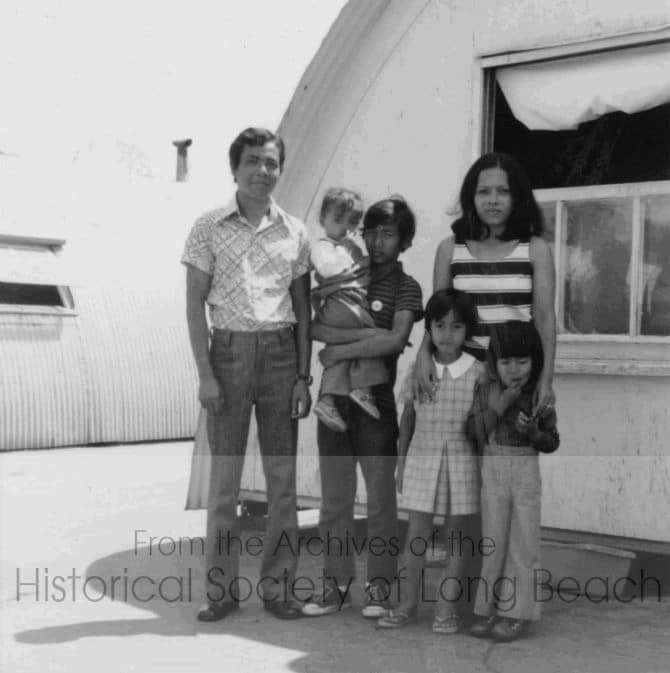

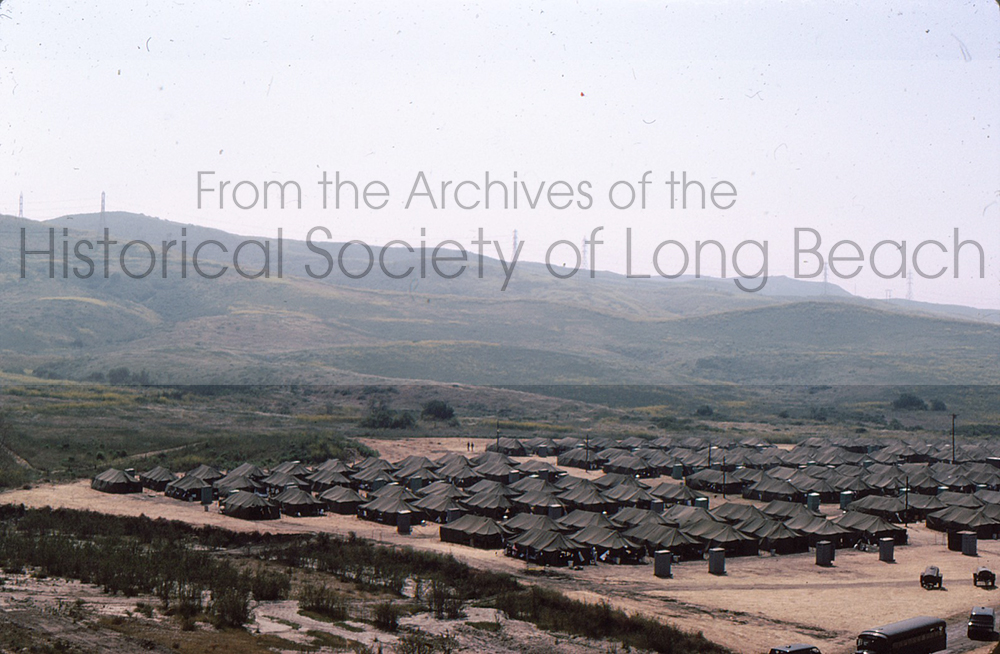

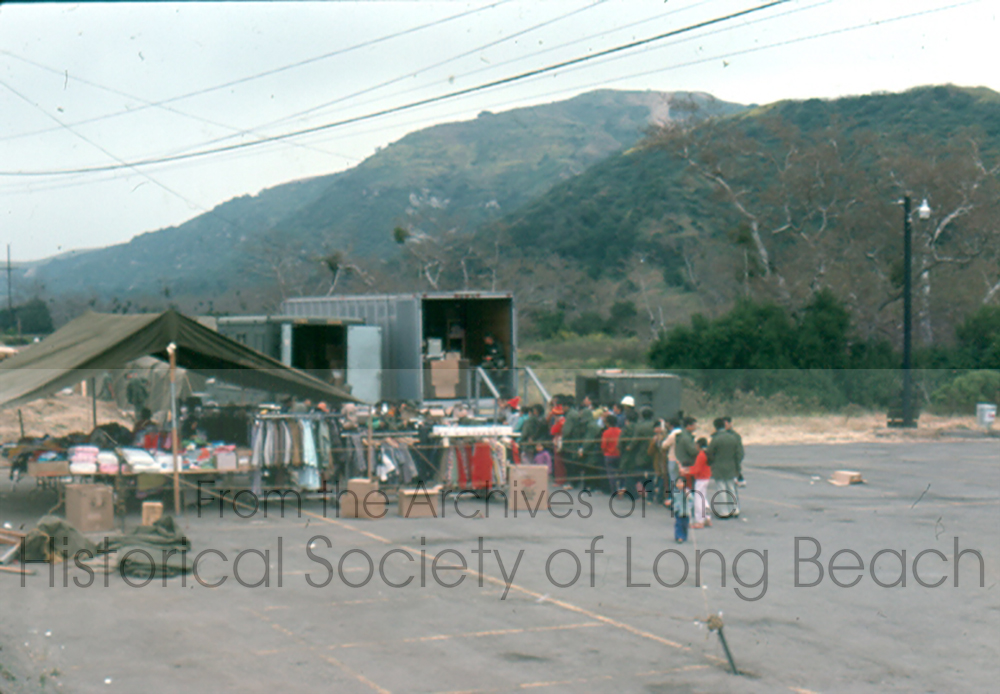

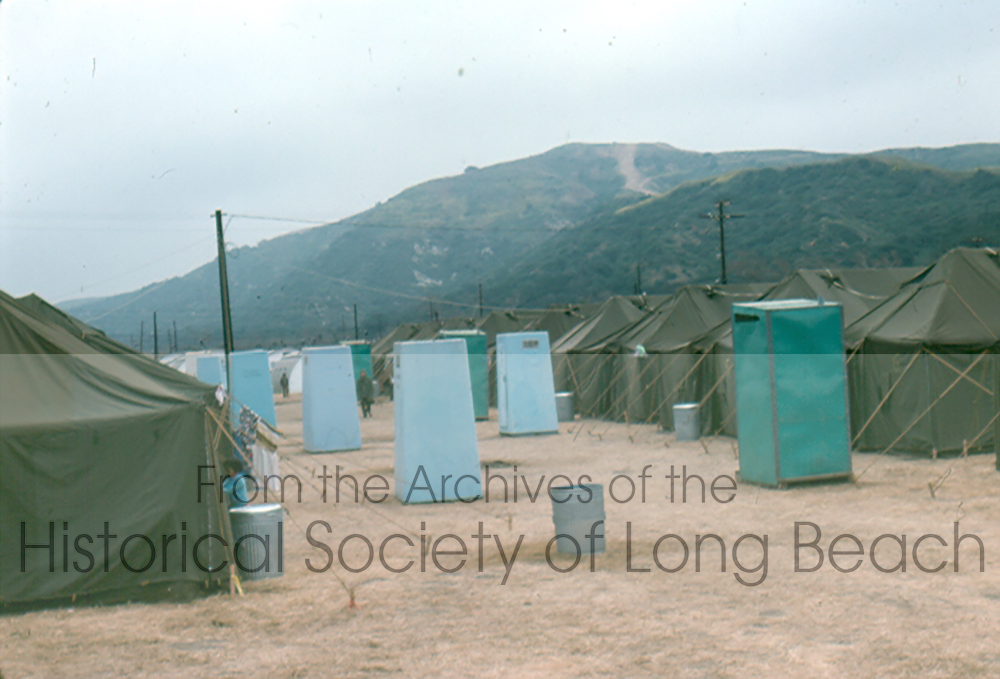

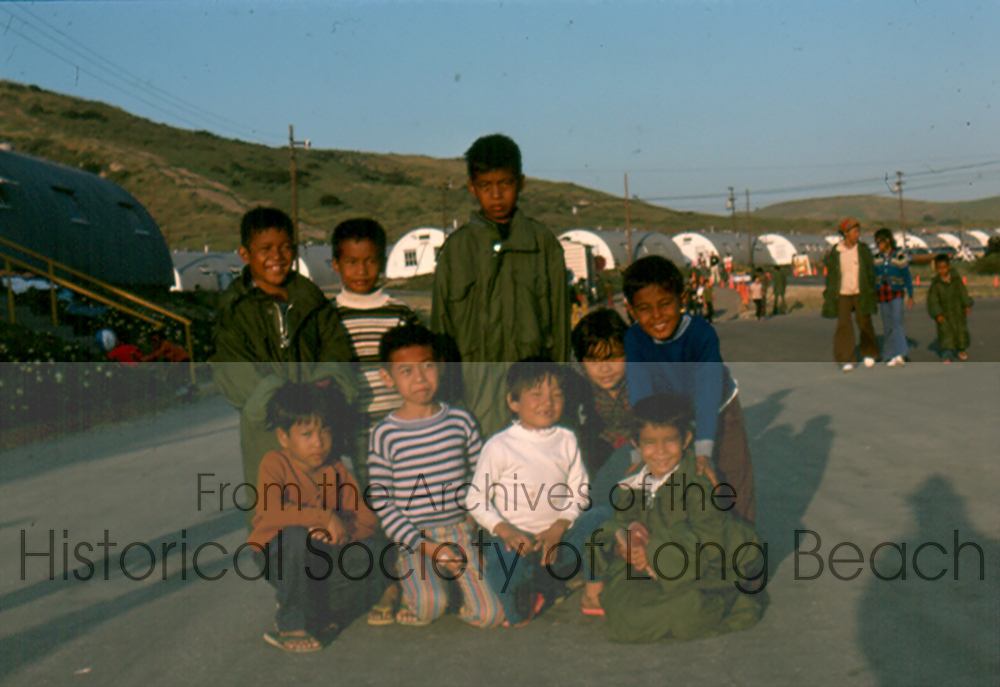

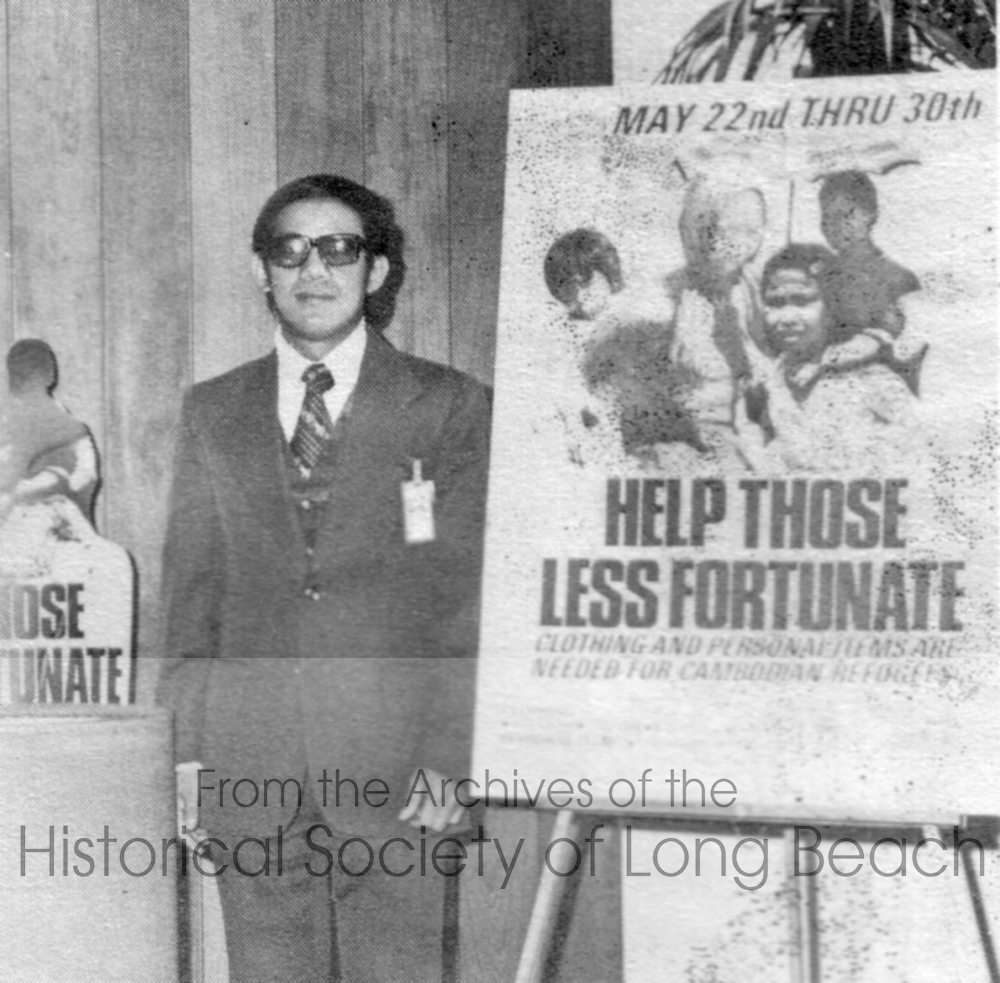

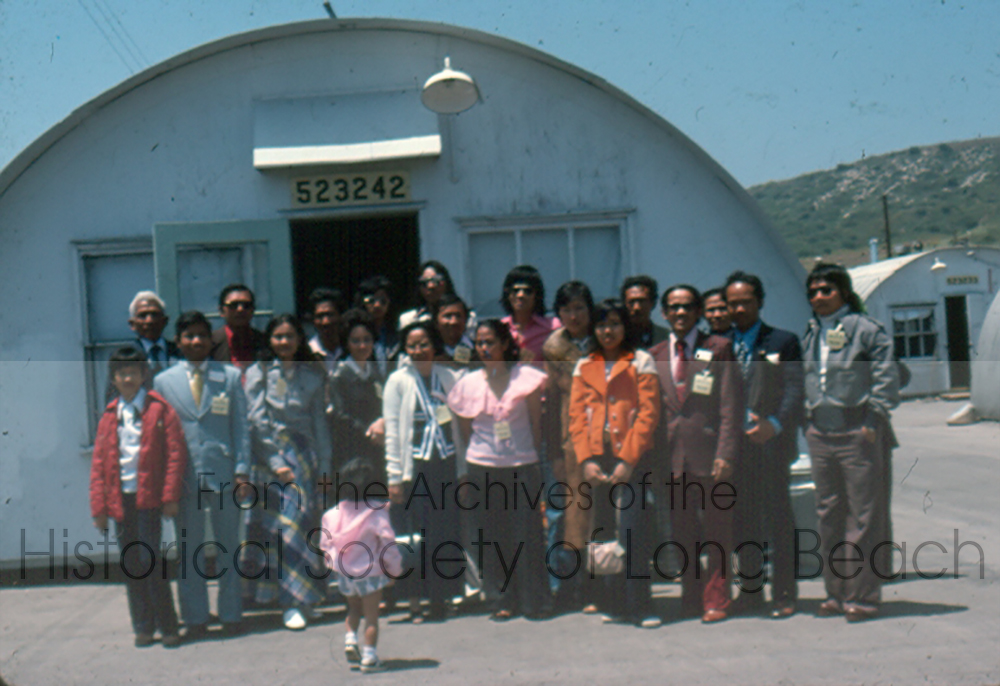

Beginning in April 1975, about 4,500 Cambodians were evacuated to the United States along with 125,000 Vietnamese and 80 Hmong and Lao. Two military bases processed the evacuees arriving from Southeast Asia: Fort Chafee, Arkansas and Camp Pendleton, California. Among Cambodian Americans, this group is often referred to as the “75 people,” a term identifying them as those who arrived in the U.S. before the fall of Cambodia to the Khmer Rouge and who did not live through the atrocities. Some of these early arrivals came directly from Cambodia, but many came from other parts of the world where they had been conducting business, attending school, or serving in the Cambodian military or in embassies. Suddenly cut off from all support, they no longer had a country to which they could return. Included in this number were Cambodian military personnel who were in the United States on student visas and had been directed to report to Camp Pendleton for resettlement as refugees.

Images

Additional Resources

✧ Cambodian American Experiences (2010) Jonathan Lee, Editor

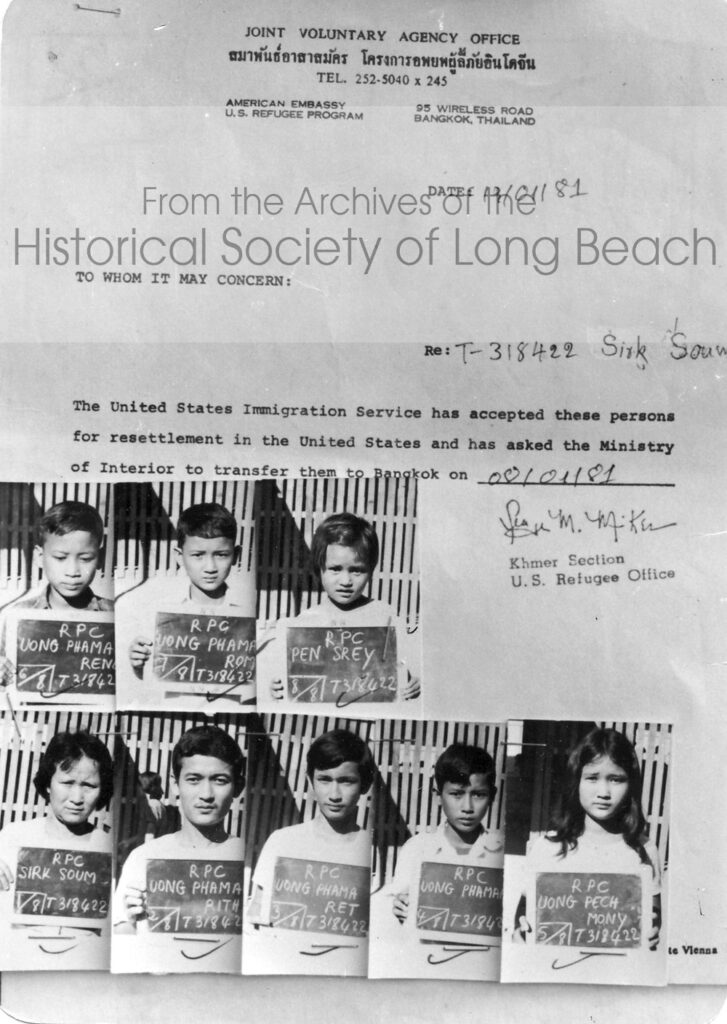

Cambodians of refugee status did not begin arriving until 1978. Very few were admitted before 1980 when large numbers were finally cleared to be accepted. Among Cambodian Americans, this group is generally referred to as “the after 80s people,” a label which not only reflected the chronological distinction between the groups but was also a statement about the substantial emotional and social differences between the two groups. The after 80 people came from a variety of backgrounds, over half from villages where the major occupations and life experiences revolved around agriculture and fishing.

Images

Personal Accounts

Additional Resources

✧ The U.S. Refugee Act of 1980

✧ Oxford Research Encyclopedias: “Cambodians in the United States”

SECONDARY MIGRATION

The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) wanted to avoid putting too much stress on any single area of the country with the large influx of new refugees, so a program was designed to “scatter” newcomers across the country into small and medium-sized cities with good potential for employment. However, most refugees were traumatized, and few spoke English. They needed and wanted to find extended family and friends to help rebuild their lives, so most moved to cities where there were more Cambodians and communities were beginning to form.

Personal Accounts

Additional Resources

Many Cambodians who came to the U.S. a refugees came because they felt they had no other choice. Every aspect of Cambodian lifeways had been destroyed. Families had been separated and family members were lost or dead. Homes, animals, roads, all forms of transportation, markets, schools, banks, hospitals – everything – everywhere – had been wiped out. Fearing for their lives, many Cambodians sought refuge elsewhere rather than attempt to rebuild lives in Vietnamese controlled Cambodia.

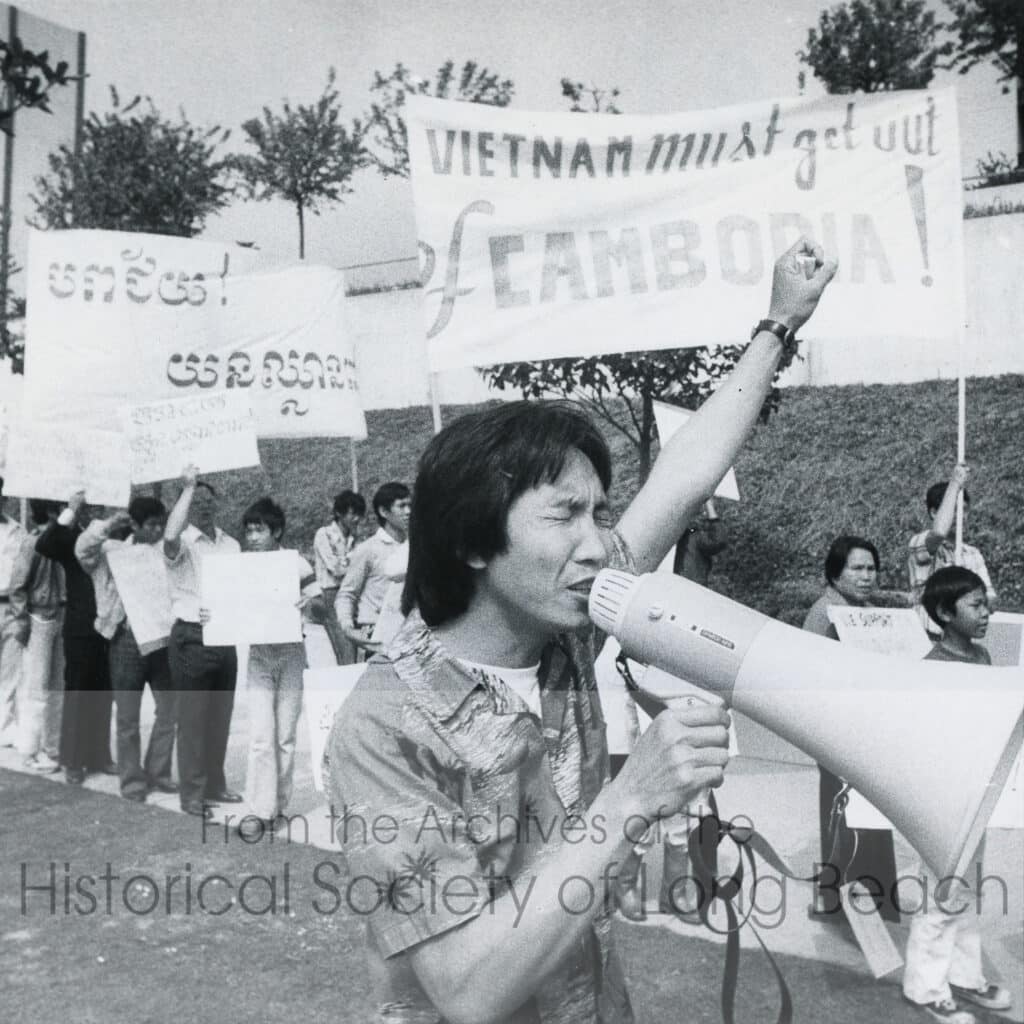

Nevertheless, many refugees hoped to return to their homeland someday and they were publicly vocal about their distress over what was happening there. Many hope to persuade the U.S. to take action. For more about Cambodian American activism see “Global Awareness and Cambodian Activism/Advocacy 1975-1979.”

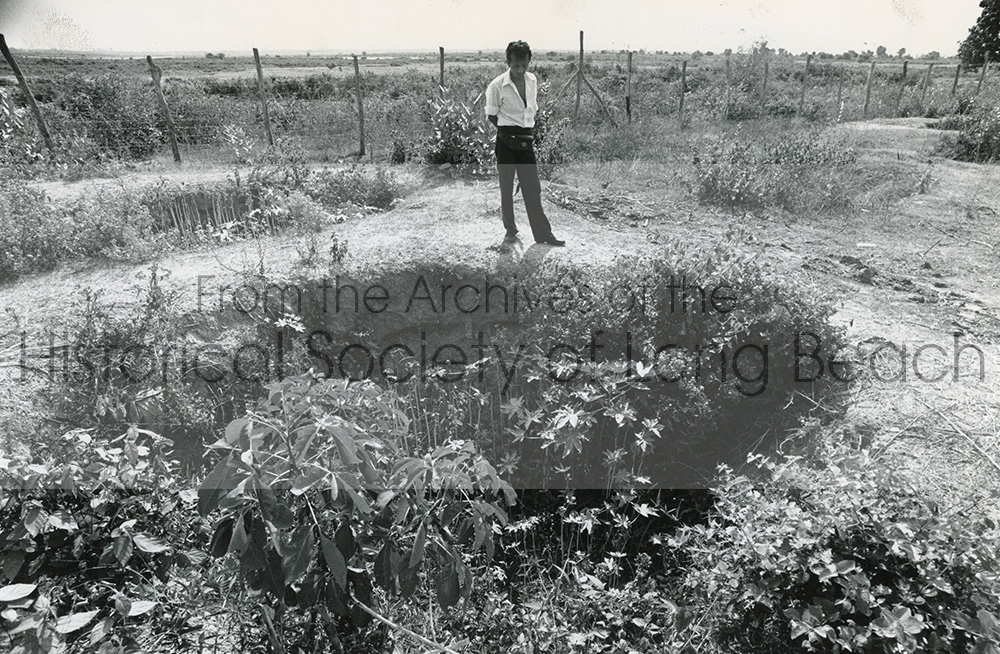

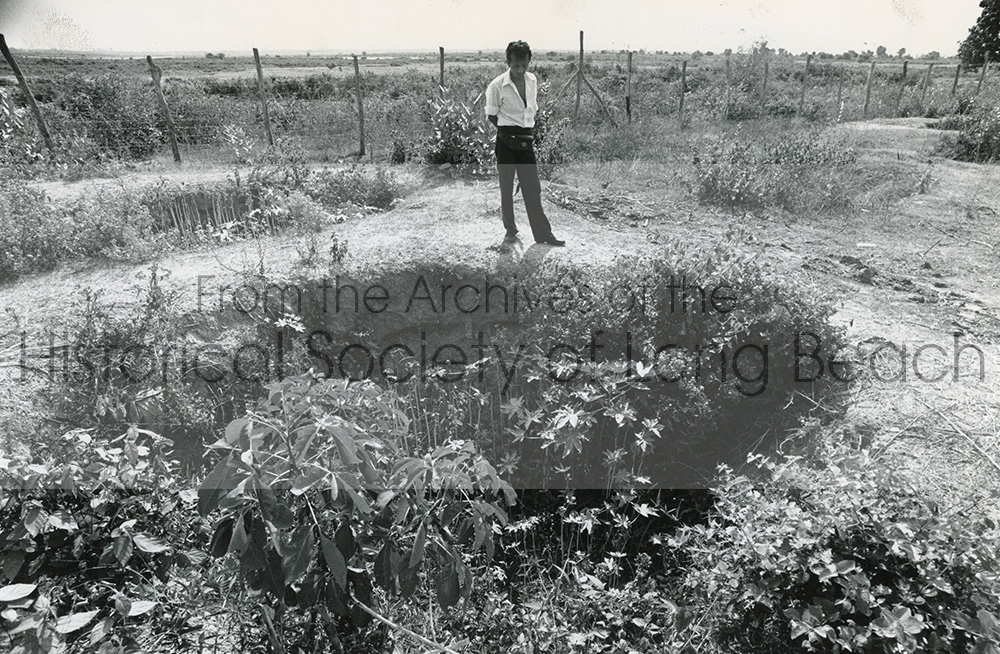

As Cambodia re-opened, Cambodian Americans began going home to find family, assess the damage, and bring aid. The country was slowly rebuilding its infrastructure (e.g. food production, communications, roads, schools, local markets, health care, banking, business, etc.) from nothing. It was often not safe to travel due to banditry, poor and dangerous transportation, and the millions of landmines the Khmer Rouge had buried that remained in the jungles and around the cities.

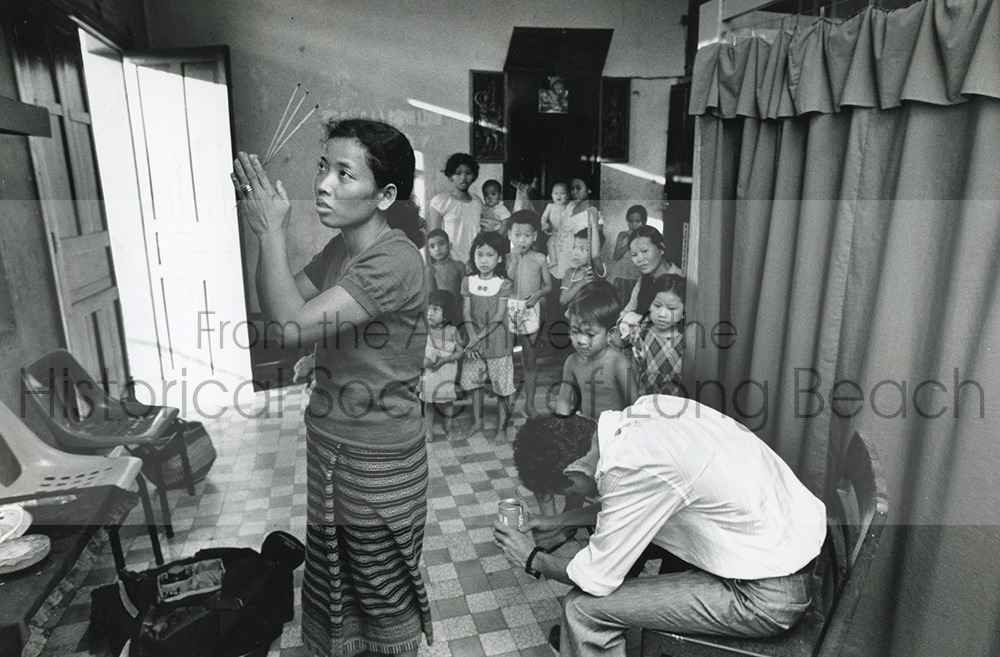

In 1989, Long Beach’s local paper, The Press-Telegram, featured a story of one man’s journey back to Cambodia to reconnect with family and a country he feared returning to. Chantara Nop is among the Cambodian refugees who worked in the Long Beach Cambodian community. He was an actor and he influenced many people’s impressions of Cambodians, especially in the early years of rebuilding community. Below is The Press-Telegram editor’s note describing the 4-part series represented as chapters.

RETURN TO THE KILLING FIELDS Press-Telegram (1989)

Editor’s note: Chantara Nop is torn between two worlds – a cruel Cambodia, where his mother and sisters struggle to survive, and a challenging Long Beach, where he is tenaciously building a a new life with his wife and children. It’s a conflict shared by many of the more than 40,000 Cambodian refugees living in Long Beach, the largest community of Cambodians outside their homeland. Yet, fearful they will be killed if they return to their native country, few have bridged the two worlds. Nop is one who did. 10 years after he escaped, a 34-year-old long Beach social adjustment counselor returned to his homeland in February accompanied by a Press-Telegram reporter and photographer. After an agonizing farewell to a family he may never see again, he came back to Long Beach in March. During the next four days the Press-Telegram will chronicle his wrenching Odyssey. Story by Susan Pack and Photographs by Bruce Chambers.

Images

Chapter 1: The Journey Begins

Describes the journey to see his family; the memory of his near death; anguish of losing family; the pain of not seeing family still alive.

Documents

✧ Cambodian Odyssey: Chapter 1

Chapter 2: Reunion at Last

Follows Nop as he reunites with his mother and other family members.

Documents

✧ Cambodian Odyssey: Chapter 2

Chapter 3: The Faces of Death

Follows Nop as he visits the killing places in the countryside and Tuol Sleng, the Phnom Penh high school that became a Khmer Rouge torture center and prison. Family members also recount near death experiences at the hands of Khmer Rouge soldiers.

Documents

✧ Cambodian Odyssey: Chapter 3

Chapter 4: The Agonizing Farewell

Nop and family leave each other and feel the pain of not knowing if this is the last time they will meet.

Documents

✧ Cambodian Odyssey: Chapter 4