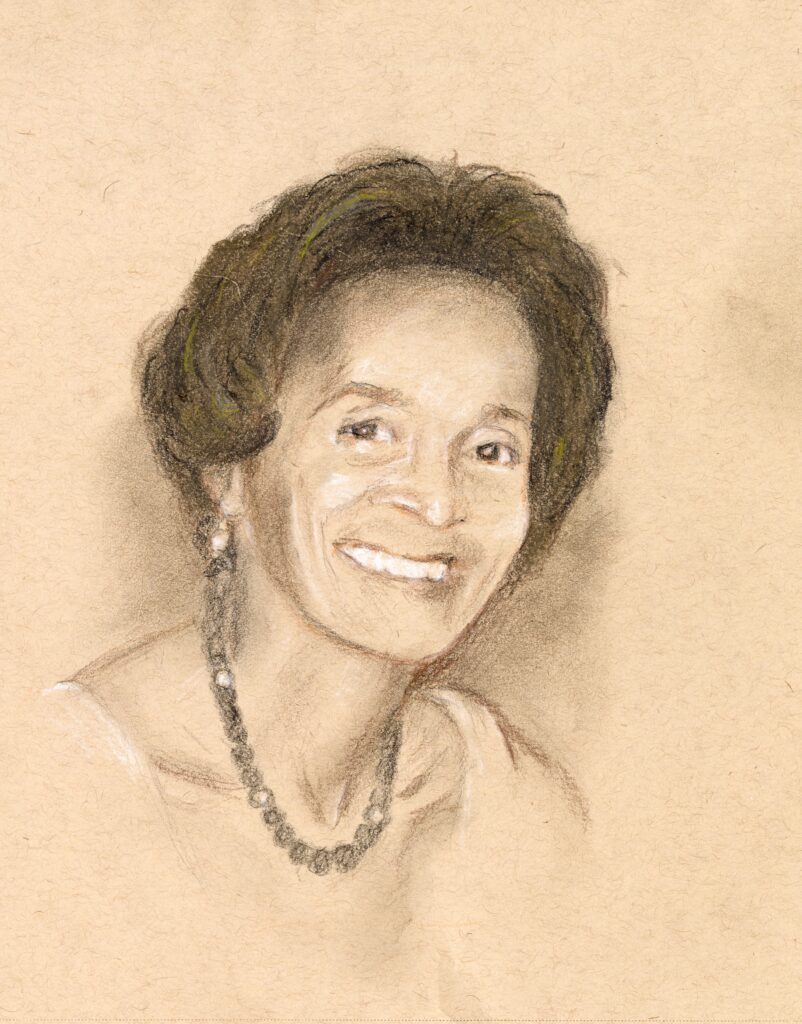

Long Beach Civil Rights Mother, War on Poverty Leader

By Karen Harper

Dale Head Clinton was born in Tupelo, Mississippi in 1927. Her father Bennie Head fled Tupelo after he stood up to his abusive boss. He headed to Chicago around 1940 where he found steady work at Wonder Bread. Dale followed him 6 months later, and two months later her mother Sally and three brothers joined them. The family left right in the middle of the Great Migration of African American families out of the South (1910 to 1970). Even though Chicago Blacks were only allowed to live in crowded designated areas, work was more reliable, and life was better.

As a young woman, Dale was aware of community needs. She called herself, “the town crier,” raising money for neighborhood people, for funerals, and other crises. When Dale graduated from Phillips High School, she attended Wilson Community College looking for a rewarding career path and considered law; but she met James Clinton, her brother’s military friend, married, and began a family.

In 1959, Dale “faced the decision of what to do.” She decided she “had to get away” from a husband with an alcohol problem. She found refuge with an aunt, and other family members in Long Beach. Dale and her children, Latrice, Darlene, Debra, and Jimmy took the El Capitan train with their possessions in two trunks. Family found them a cute little rental house, furniture, kitchen items, even a washing machine. Dale obtained a “non-union” job assembling televisions at Packard Bell in Los Angeles. Her youngest son was born in 1961 during a failed attempt at marriage reconciliation. Dale went back to work at a job close to home as a maid in the Lafayette Hotel. Childcare was consuming a huge portion of her income. Friends explained that government support is designed to help families through difficult times. She was convinced to apply for welfare benefits “because I did not want delinquent children.”

Although civil rights laws are still in the process of being enacted and almost sixty years later, Dale Clinton has done more than her share. In 1963, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was organized by a coalition of civil rights groups such as SNCC, CORE, SCLC, NAACP, and others. Among the speakers was a young John L. Lewis and Dr. Martin Luther King giving his “I Have A Dream” speech to around 250,000. The multi-racial crowd called for an end to racism and opening of job opportunities for African Americans and minorities everywhere including Long Beach.

A year later in 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin. Soon after, the Economic Opportunity Act (EOA) and other laws under the “War on Poverty” concept were enacted. The EOA was federal legislation aimed at improving education, health, employment and general welfare for impoverished Americans. Programs included the Community Action Program, Jobs Corps, Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), Food Stamps, Head Start, Medicare and Medicaid, and more.

In 1964, the War and Poverty programs came to Long Beach. The city is lucky Dale was introduced to the opportunities opened up by EOA programs. She became a leader in Long Beach civil rights work. As an involved parent at Roosevelt Elementary School, Dale was always raising issues. Principal Ross asked her to represent the school on a poverty program committee. She went to the first meeting not knowing what to expect, dressed in “her cute little yellow dress.” She says “the best of the best” in social services agencies were there such as Joe Brooks, Lucy Stills, Opal Jones, United Way leaders.

Everyone around the room introduced themselves with the initials of their agencies. She did not know what to say, so she said, “AFDC.” People were surprised by her honest naïve answer. Some of “the men laughed so hard, they fell out of their chairs with tears streaming out of their eyes. Afterwards, they all circled around her and welcomed her to the mission of helping people in the community. That was it, she was part of the group.” These friends kept insisting that she take a paid job with Neighborhood Adult Paticipation Project. Dale’s retelling of this story shows her humor, humility and the beginnings of her journey as an expert on racial justice and school integration.

Officials in Long Beach city government also recognized Dale’s potential and recruited her for a program at UCLA in education and human services, condensing four years of study into two. She describes that experience as “a bunch of young folks determined to rescue the world.” Soon she was recruiting parents and children for the first Head Start schools in Long Beach. Her son was a student in the first class. For a year she was a Western Region integration trainer under the UCLA program, traveling to Arizona, Nevada, California, and Hawaii. She trained principals, teachers and staff in race relations in preparation for integration in local Los Angeles area schools. She recalls traveling at night to places such as Pasadena “to teach people to treat African Americans and Latinos like they would want to be treated themselves.”

In one of her proudest moments, Dale wrote a letter to President Lyndon Johnson to save funding for Head Start. He answered her letter and it was recorded in the Library of Congress. Her letter was published in the Press-Telegram, and dailies all over the country. That letter helped insure continued funding for Head Start.

After work in important and challenging integration training programs, Dale finally agreed to go to work for the City of Long Beach. Her first assignment was at Cal Rec by Polytechnic High School. She laughs remembering that city officials were “afraid” of Black Panther Errol Parker and others who provided community services out of Cal Rec. She was given funds to compete with them. One of her projects was to co-ordinate with staff at Cal Rec, MacArthur Park and Martin Luther King Park on youth field trips to places such as the San Diego Zoo and the Botanical Gardens, exposing kids to a wide range of experience. She recalls sometimes filling ten or fifteen buses, heading down the freeways, taking children on adventures. In another example, as homelessness increased, the city did not have services. Dale noticed an old hotel on Pacific Coast Highway and convinced the city to turn it into a homeless shelter. She also was involved in developing other programs for impoverished families such as utility subsidies.

Dale’s commitment to racial integration included improving race relations. After tensions exploded in 1966 at Polytechnic High School, inter-racial groups formed to find solutions. FREE was organized by Sharon Cotrell who was a beloved member of Dale’s extended family, often coming to dinner and caring for the kids. The group met at the Long Beach Community Improvement League hall. Another group with far reaching influence was the Poly Community Interracial Committee (PCIC). It was formed in 1966 by LB Unified School District and the Los Angeles Commission on Human Relations to calm racial tensions and work on issues of integration of students and staff. Along with Dale, some of the PCIC members were Bill Barnes, Carl Cohn, Polly and George Johnson, Mary Dell Butler, and school board member Liz Wallace. They met in secret amid threats of violence from white supremacists. The committee moved from meeting place to meeting place, sometimes in people’s homes. The story goes that Mary Dell Butler’s husband Richard often provided security for the meetings with a shot gun across his knees on front porches. The committee helped develop the magnet school programs to integrate the schools and prevent closure of Poly High School. The PACE Magnet Program was finally implemented in 1976. As a result, Poly has remained the pride and joy of alumnae of all racial and ethnic backgrounds and is recognized as one of the best high schools in the nation. In many other cities, the original high school was shut down to force integration. The alumni of Poly were not going to let that happen here.

The Historical Society of Long Beach presented a panel discussion on the history of the PCIC in 2004. At the event, Dale described teaming up with friend Mary Dell Butler to confront racism. They had a spontaneous, “Good cop, bad cop” approach. Dale says her younger self was angry and let words fly that “even Popeye didn’t know.” Mary Dell would step in with a soft voiced approach to conciliation.

Dale spent the rest of her career serving in various departments within the city government. She worked downtown in community relations for twenty-two years and ended her career in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Marine. She has been an integral part of the integration of city government, opening up career paths for the diverse population of one of the most diverse cities in the United States.

Dale endured many tragedies. Her mother died when she was a young adult in 1947. She fled a marriage across the country with five children. Her beloved son, an accountant, was murdered. In 1991, she survived breast cancer and a mastectomy. Last year her daughter passed away. Family, friends, and religion has been a sustaining force in her life along with a joyous home filled with great-grandchildren. Her daughter and her husband are ministers in their “Jesus is the Answer” church in Compton.

Dale is known as one of the respected “Mothers” of the African American community. When Dale was recently hospitalized after a fall, worry and best wishes for her recovery were far and wide. Dale is back– feisty, thoughtful, wise, and full of fun and laughter as she reaches toward ninety-four.

Julie Bartolotto, Project Director