Cambodians were forever changed by the brutal takeover of their country by the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975. The Khmer Rouge forces led by Pol Pot, attempted to take Cambodia back to a time before western influence. To accomplish their objective, they systematically cleared the cities and murdered the most educated members of society. Once forced into the countryside, Cambodians lived in abysmal conditions lacking adequate food and health care and were compelled to work in segregated camps for fear of beatings. By the time the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia and brought an end to Khmer Rouge control over the country in 1979, nearly 2 million Cambodians had died. The turmoil and pain did not end, however, in 1979. Cambodians fearing more persecution, starving to death, and running from the advancing Vietnamese army fled to the Thai-Cambodia border where refugee camps established earlier began to overflow. Once in the camps, they faced an uncertain future. Every Cambodian who survived the “Pol Pot time,” as it is often called by community members, lost family members and friends or had been separated from close kin. The arduous process of rebuilding lives and reconstructing cultural traditions began in the camps. The only hope Cambodians had was to be chosen for resettlement in France, Canada, Australia, or the United States, the main countries accepting Southeast Asian refugees.

This section presents some of the geopolitical context of Cambodia’s history from 1950-1980.

Videos

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll, depicts Cambodia’s changing music scene from the 1950’s through the Khmer Rouge period, when art and music were used to support politics and ideology.

Additional Resources

✧ Chronology of Cambodian Events Since 1950 – Yale University’s Genocide Studies Program

✧ Cambodia profile – Timeline – “A chronology of key events” – BBC News

The Cold War (1946-early 1990s) marked a time of global and regional conflicts. The political and ideological rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, and their aligned nations, divided allegiances between the so-called Free World and the Communist Bloc. Cambodia, under the leadership of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, maintained a policy of neutrality. However, this neutrality was violated as the war escalated in neighboring Vietnam. The United States conducted secret bombings of Cambodia to cut off the supply routes of the communist North Vietnamese. As the war continued to spill into Cambodian territory, the people suffered, contributing to the rise of the Khmer Rouge, a communist insurgent group responsible for mass atrocities.

Additional Resources

✧ The Khmer Rouge in a Cold War Context – David Chandler, historian

✧ Cambodia 1972-75 / Thai Border 1980 – Colin Grafton, photographer

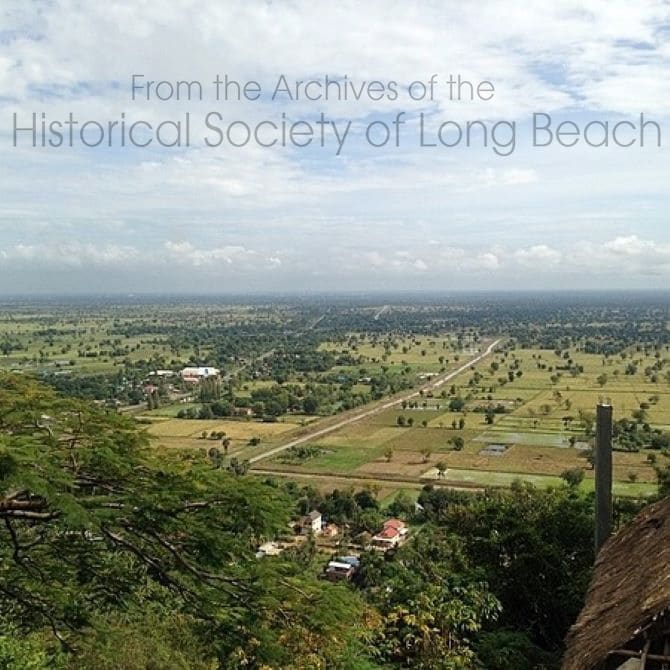

This section provides historical documentation of the impact of U.S. bombing of Cambodia, including how the bombing helped create the conditions for the rise of the Khmer Rouge. Ongoing military conflict between the U.S. and Vietnam resulted in the U.S. conducting bombing raids throughout eastern Cambodia which killed an estimated 50,000 to 150,000 Cambodians and exacerbated civil conflict within Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge used U.S. bombing to recruit Cambodian villagers into their revolutionary cause. The findings here are based, in part, on historical mapping that makes use of declassified government documents from that time.

Videos

Additional Resources

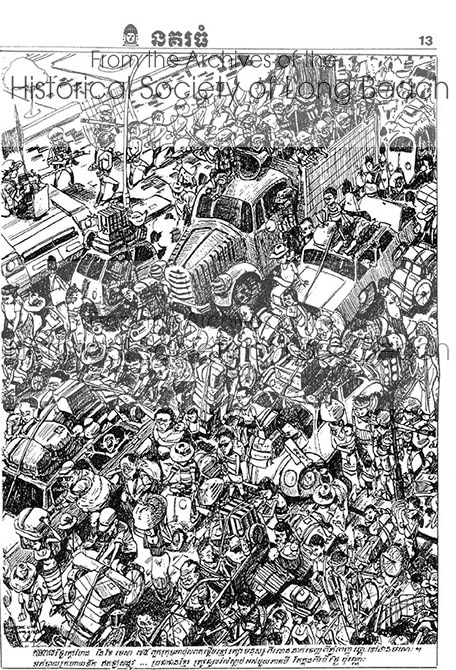

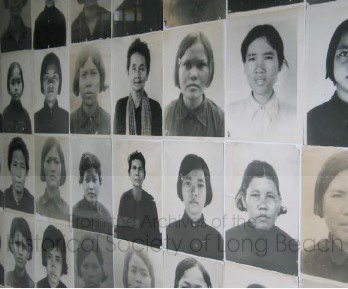

On April 17, 1975, after years of foreign warfare overflowing into Cambodia and civil war raging within its borders, the Khmer Rouge took control of the country. Seizing Phnom Penh, the capital city, Khmer Rouge soldiers evacuated its residents, forcing them from their homes and into rural areas where they were separated from family and forced into labor camps. The Khmer Rouge implemented a radical revolutionary plan for the country with hopes to transform Cambodia back into the agrarian society of its past and rid it of class distinctions. To achieve this, they halted all economic activities and shut down schools, religious activities, hospitals, and government services. All forms of entertainment, reading, writing, travel, and the arts were banned, with the exception of Khmer Rouge revolutionary performances. For ordinary people, life revolved around manual labor, working ten to twelve hours per day, year-round, without proper food, medicine, or rest. Anyone who resisted or opposed the Khmer Rouge policies was at risk of being arrested, imprisoned, tortured, or executed. By the end of their reign, it is estimated that between one-fifth to one-quarter of Cambodia’s total population (approximately 1.7 million people) had died as a result of starvation, exhaustion from forced labor, disease, lack of proper medicine, and outright murder.

Images

Videos

Additional Resources

✧ A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979) – DC-Cam

✧ A Teacher’s Guidebook – DC-Cam

✧ The Cambodian Genocide Survivors Stories & Testimonies

✧ “Pol Pot’s Shadow” – Frontline Report – 2002

✧ Suggested Reading: A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979) – David Chandler (2020)

When the Vietnamese entered Phnom Penh in early 1979, the Khmer Rouge was forced out of power. Many Cambodian survivors saw this as a liberation and celebrations ensued. In the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge, survivors were left to pick up the pieces of their lives, families, culture, and country. Despite initial jubilation, for many survivors there was not much left for them in Cambodia. Virtually every survivor lost loved ones, their homes, livelihoods, and possessions. Mass destruction of villages and cities from ongoing warfare leading up to, throughout, and after the Khmer Rouge period left most survivors without a home to return to once freed from forced labor camps or prisons. Faced with few options, approximately 600,000 survivors fled to refugee camps in neighboring countries, seeking assistance and, for some, the possibility of a fresh start in a new country.

Documents

✧ A third force in the jungle – Far Eastern Economic Review, Oct. 18, 1979

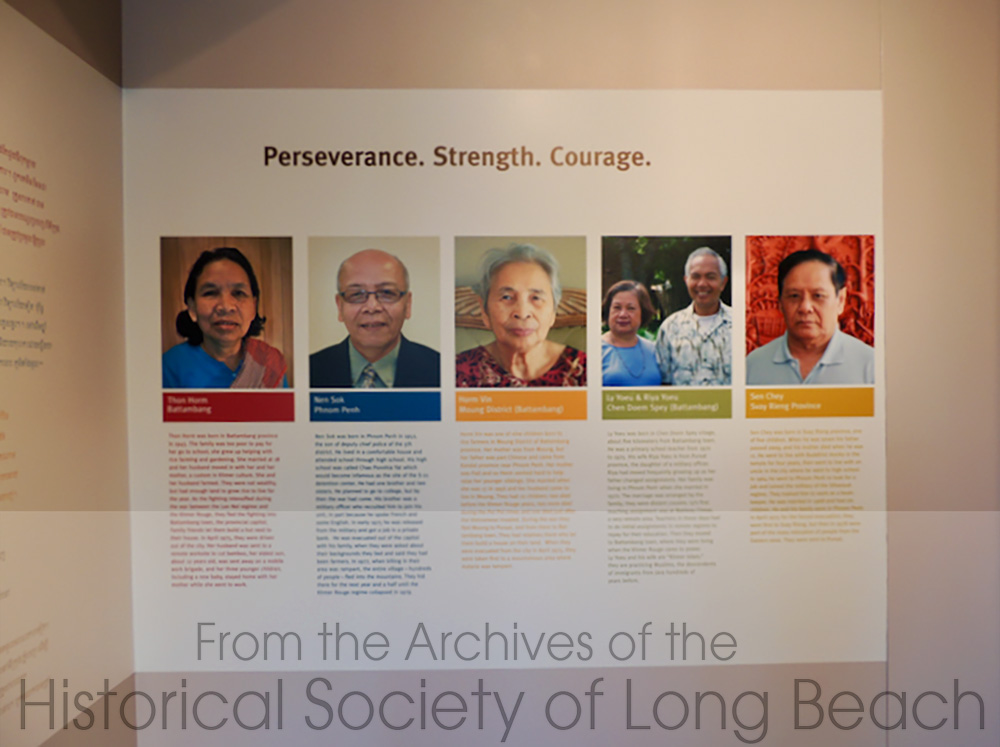

This section features a selection of oral histories given by Cambodian American survivors who were children when the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia in 1975.

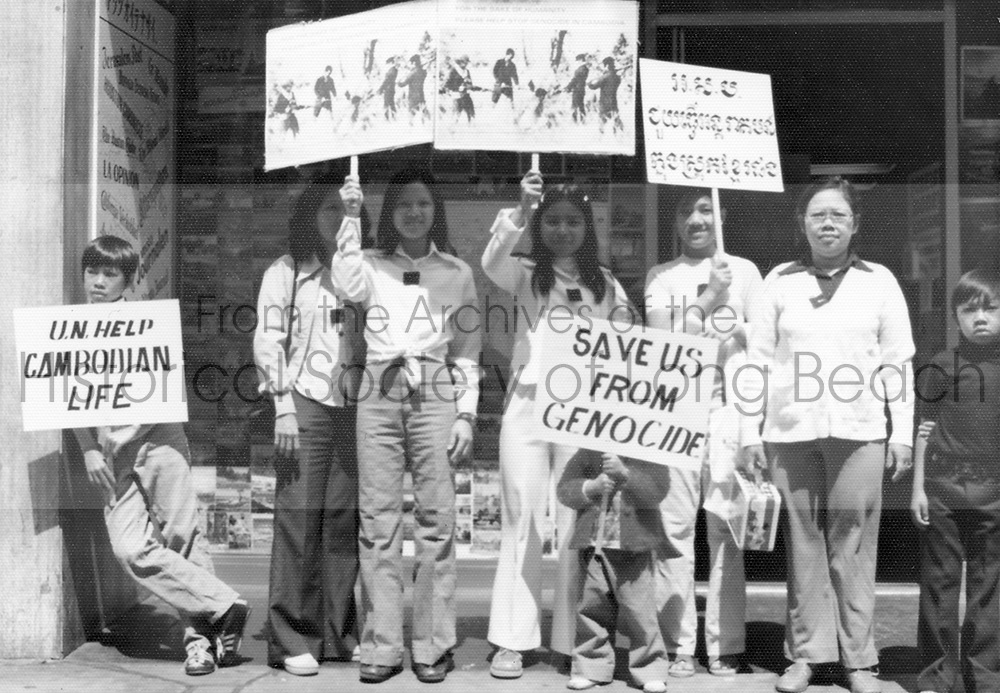

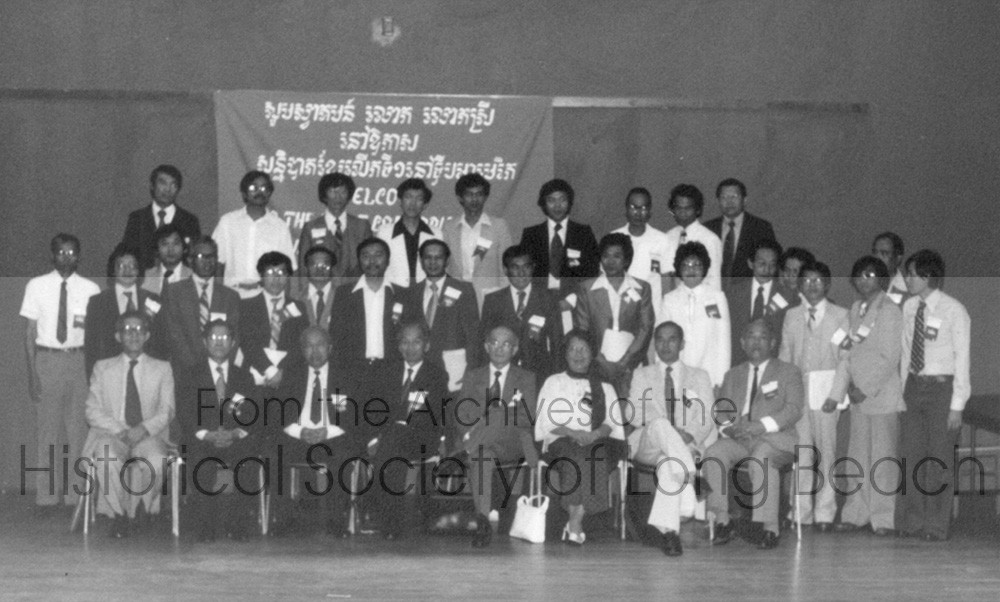

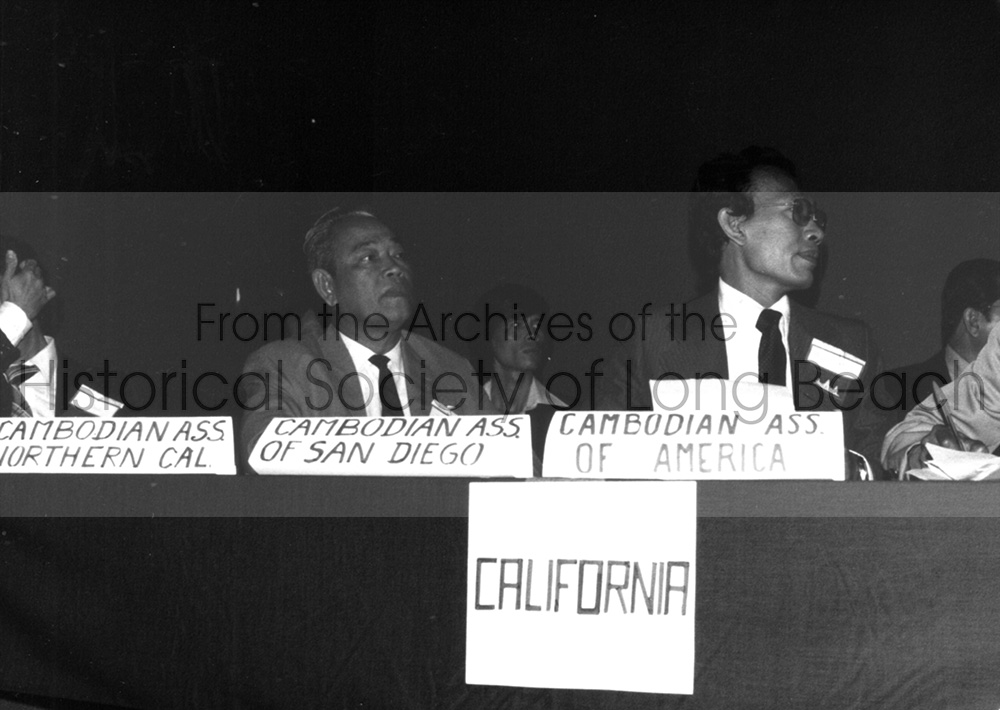

As reports from survivors of the Khmer Rouge atrocities leaked out to reporters and were published in the New York Times in July 1975, Cambodians in the U.S. organized national conferences and protests. This section presents a small sample of these activities.

Documents

✧ The General Assembly Mission Council – Position on Cambodia July 19, 1975

Protests to Stop Genocide

Although the Khmer Rouge closed Cambodia’s borders after taking control of the country in April 1975, a few people were able to escape into Thailand fairly early (see Sophy Khut in Oral Histories). Their stories of the atrocities were published in the New York Times in July 1975. Cambodians from Long Beach and the surrounding areas organized a protest in front of the United Nations building in downtown Los Angeles (Courtesy of Cambodian Association of America).

Images

Documents

✧ Congressional Record – Humanitarian Need of Cambodians in Thailand Jan. 21, 1976

Videos

1976 U.S. National Refugee Conference

As the situation in Cambodia worsened, delegates and representatives from Cambodian groups from across the nation worked to unite under one national organization. In 1976, the national group held a conference in Long Beach aimed toward mobilizing resources to ensure Cambodian refugees received support and understanding from fellow Cambodians and the United States.

Images

Documents

Newspaper Accounts of Cambodian Atrocities 1975-1979:

✧ Cambodia’s crime… – New York Times – July 9, 1975

✧ Cambodian refugees tell of revolutionary upheaval – New York Times – July 15, 1975

✧ Multiple newspaper articles – China Post Dec. 4 & 6, 1976 – Wall Street Journal Nov. 26, 1976

✧ Cambodians: An endangered species – Los Angeles Times – May 7, 1978

✧ A third force in the jungle – Far Eastern Economic Review – Oct. 18, 1979

The movement of the Vietnamese military into Cambodia in late 1979 received mixed emotions from Cambodians at home and in the diaspora. For many Cambodians in exile, the event was seen as an invasion by an ancient enemy. But many in Cambodia, who had lived through the Khmer Rouge period, saw the Vietnamese as liberators. These opposing points of view are the basis for areas of disagreement among many Cambodians to this day.

Images

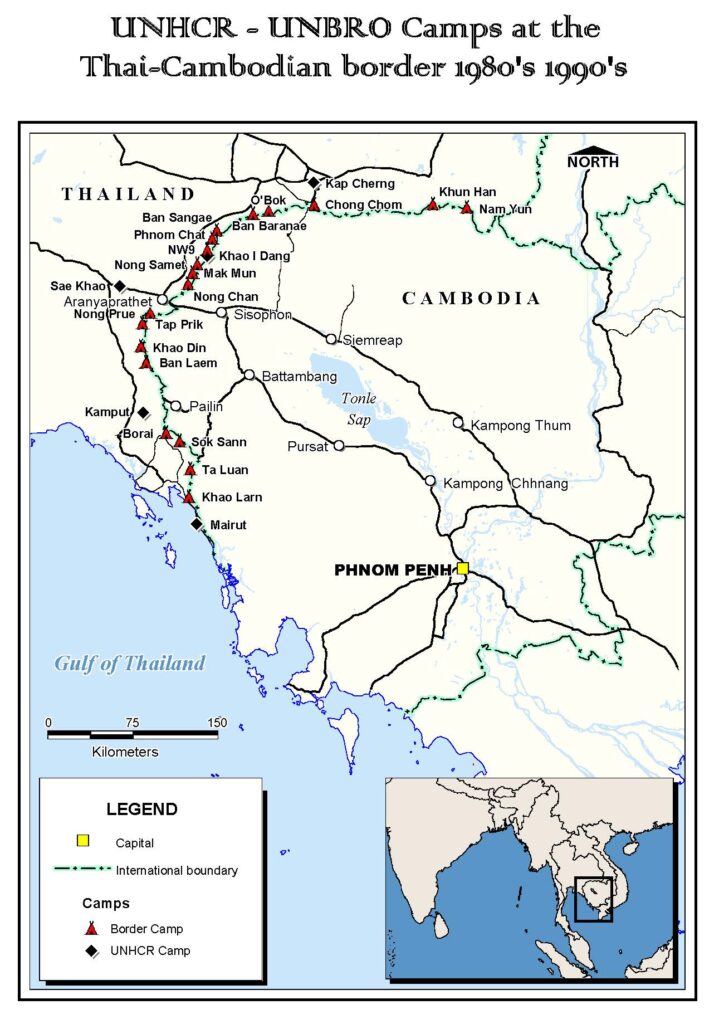

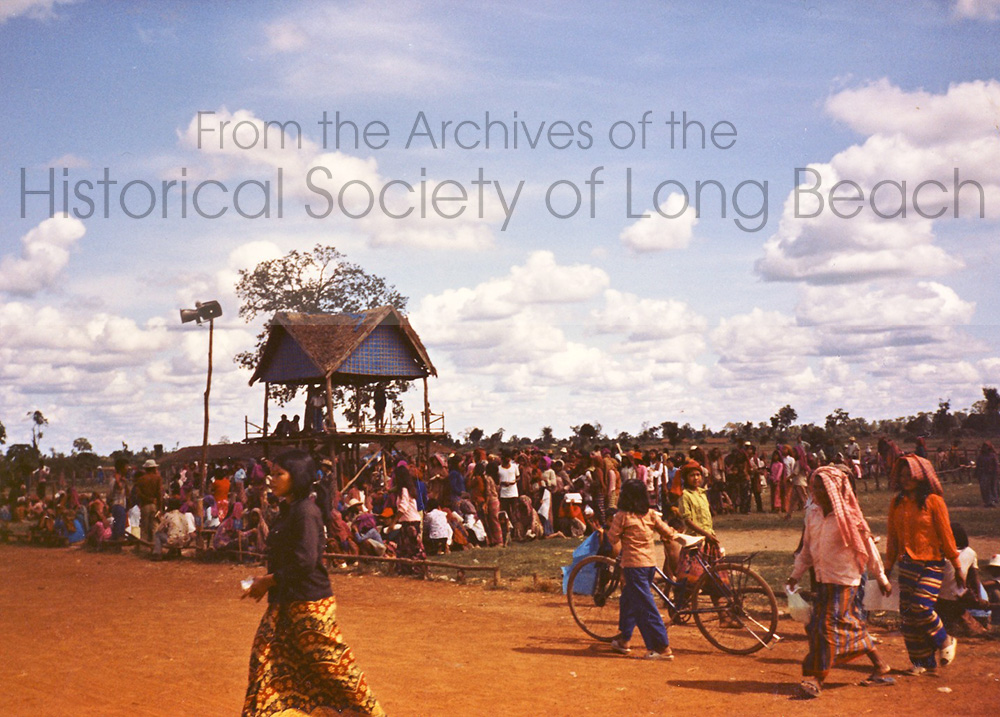

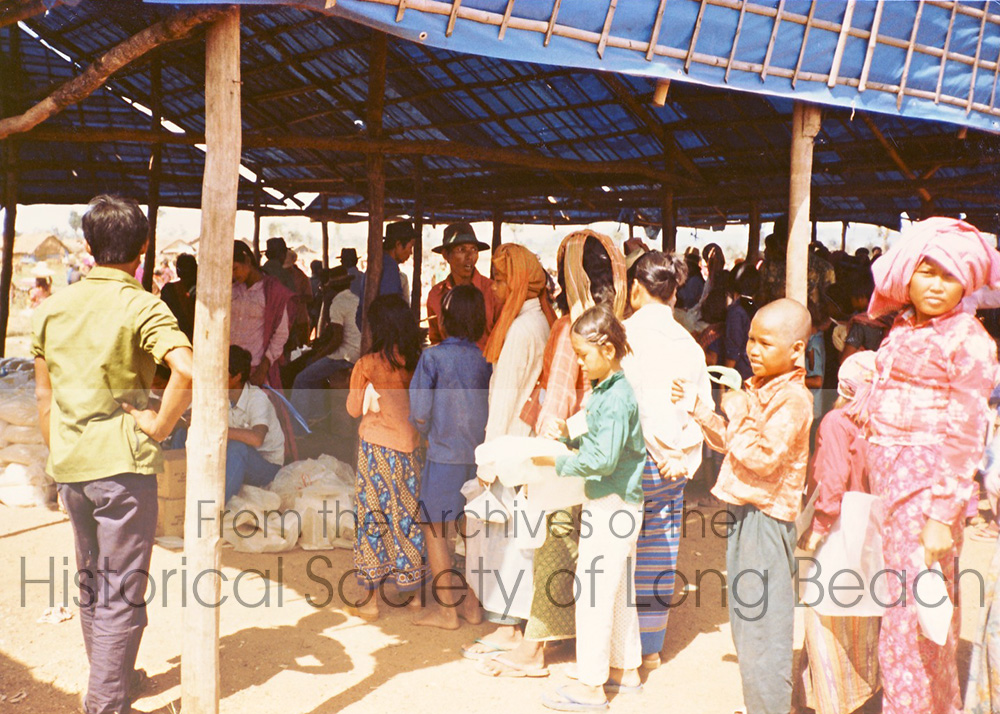

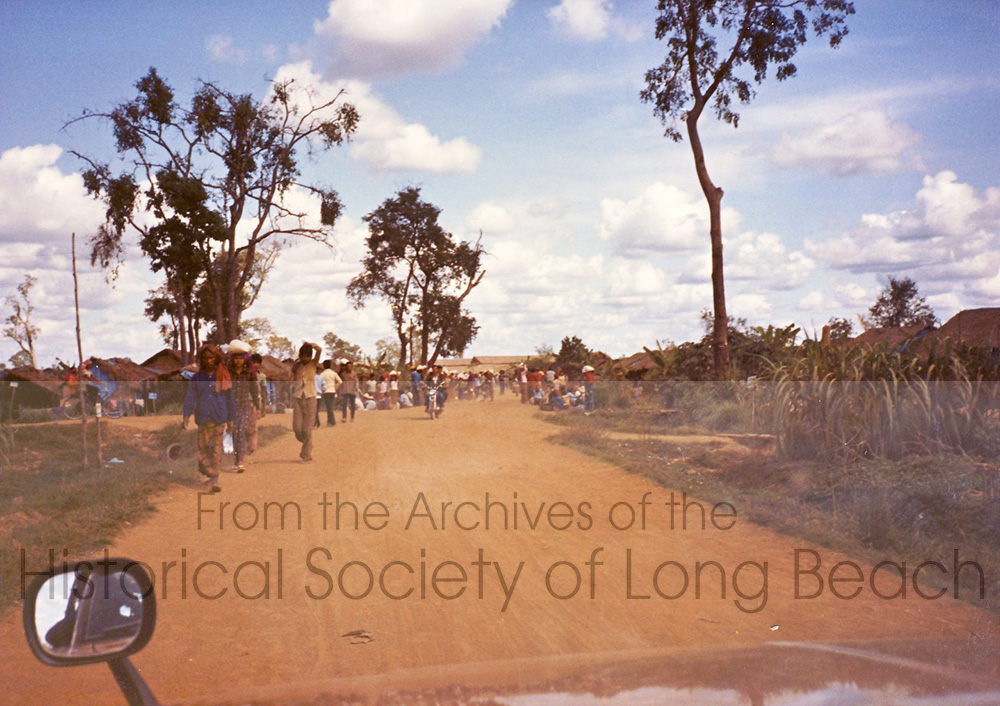

Shortly after the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia in July 1975, Cambodians began escaping across the border into Thailand. Small camps formed all along the border (see map). The greatest concentration of people and camps formed near Aranyaprathet, a Thai town just across the border from Poipet. After the Vietnamese entered Cambodia in late 1978, hundreds of thousands of Cambodians fled to the border. Among these were also Khmer Rouge soldiers who were fleeing from the Vietnamese. The major camps set up between 1979-80 were Khao-I-Dang, overseen by the United Nations Refugee Agency; Nong Samet (“New Camp”), overseen by the Khmer military; and Sakeo I & II, overseen by the Khmer Rouge. Cambodians accepted for resettlement in the U.S. were sent to processing centers in the Philippines where they learned English and aspects of life in the U.S., such as how to use a phone.

Images

Documents

Indochinese Refugee Reports May 1, 1979 – November 27, 1979:

Videos

Reuters News Report from Khao-I-Dang shortly before the camp closed:

Additional Resources

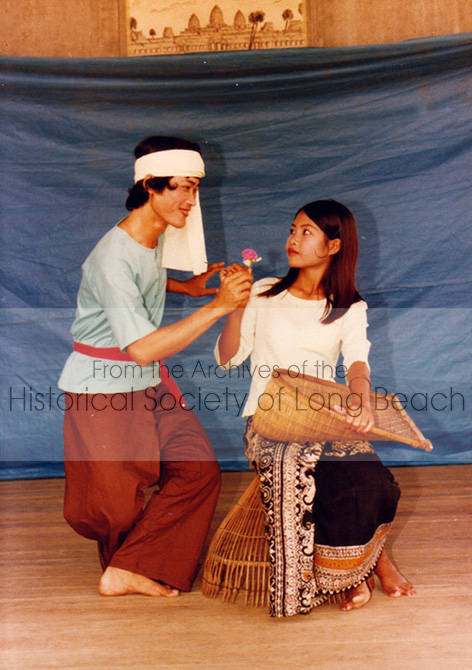

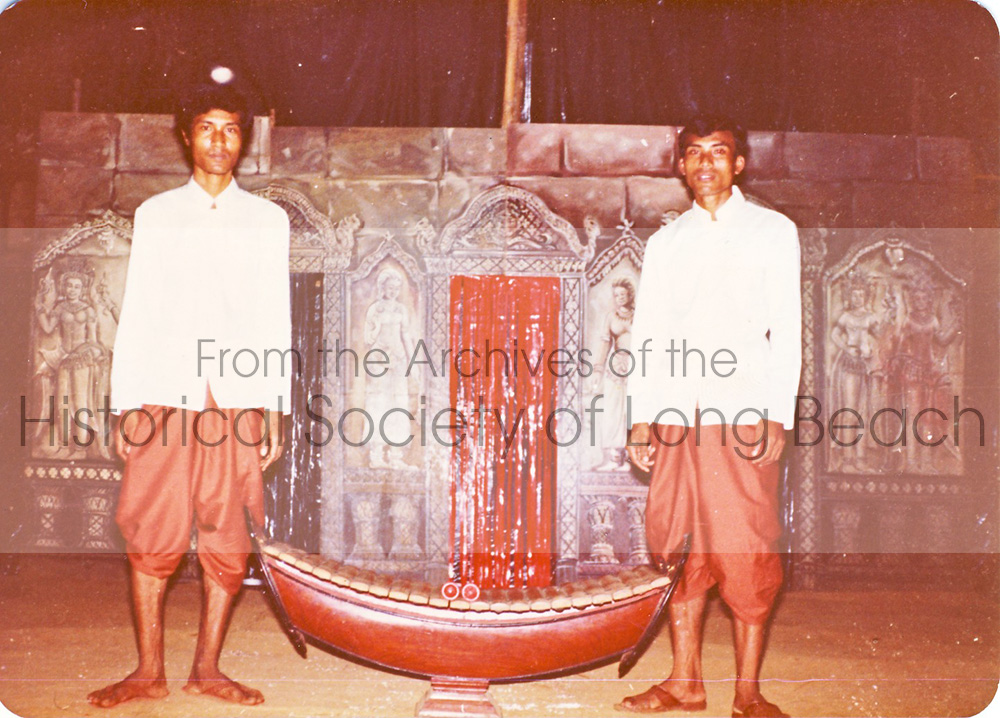

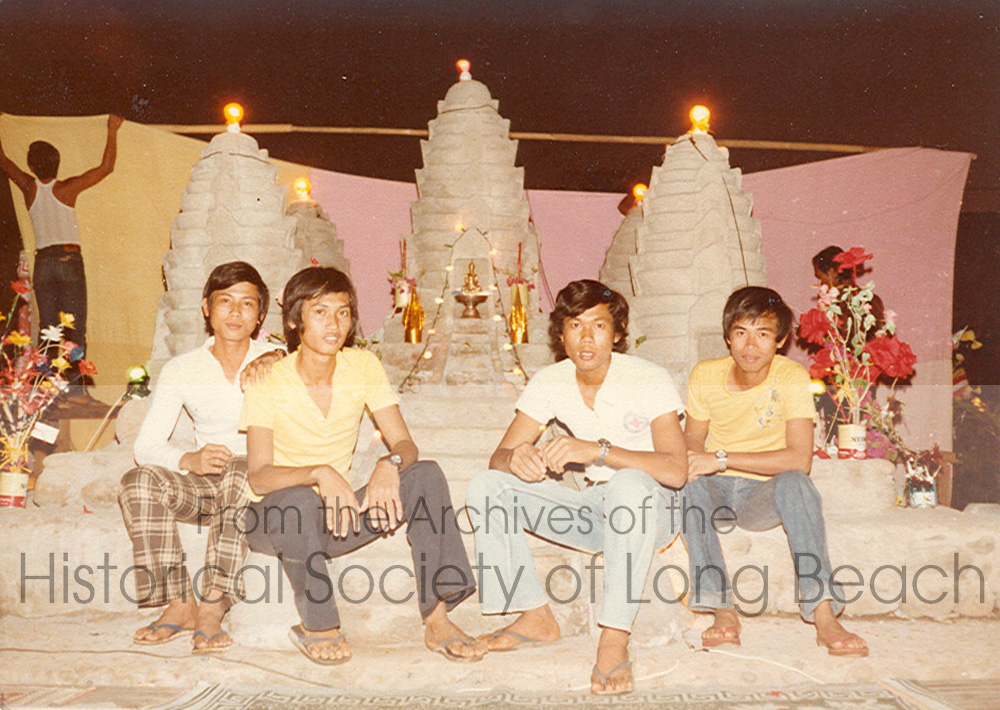

During the Khmer Rouge, key symbols of Cambodian culture were manipulated to propagate the regime’s Communist ideology, distorting its essence in the process. Once in the refugee camps, Cambodians revived their cultural heritage and symbols. Performing Cambodian traditional and popular dance and music became central to regaining a sense of belonging and hope in the wake of violence and loss. This section highlights examples of the revitalization cultural heritage heritage in the refugee camps.

Images

Additional Resources

✧ Colin Grafton – Dancers (1974)

✧ Suggested Reading: Dance and the Spirit of Cambodia – Toni Shapiro (1994)

This section provides additional resources related to Genocide and Mass Atrocities in the world. According to the U.S. Department of Justice Archives: “Genocide is defined and includes violent attacks with the specific intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.” Consequently, the two surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge, Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea were tried and found guilty of genocide against ethnic Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese but could not be charged with genocide for the deaths of nearly 2 million Khmer. Instead, they were found guilty of the lesser charges of crimes against humanity and war crimes. Many Khmer remain deeply troubled by the fact that it was Khmer who killed Khmer – their own people. Although the Khmer Rouge period in Cambodia does not strictly fit the definition of Genocide, it was a mass atrocity on a grand scale and is held to be one of the worst of the 20th century.

For more on the definition of genocide, see: What is genocide?

Additional Resources

✧ Genocide and Mass Atrocities in World History – DC Cam

✧ Genocide: Armenian, Rwandan, Cambodian, and the Holocaust – University of Massachusetts, Lowell