Cambodians are a relatively recent immigrant group in the history of the United States. The story of Cambodian immigration is very different from immigrants who came to this country before them. While most new immigrants can count on well-established communities to provide both emotional and economic support while adjusting to American life, Cambodians had no such luxury. Only a handful of Cambodians lived in the United States prior to 1975 and although they immediately extended help to those arriving in the early days, the essential networks and bridges to mainstream American life, jobs, and language had to be created.

As a result of U.S. Refugee Resettlement policies, Cambodian communities have formed throughout the the country. The largest of these are located in Long Beach, CA; Lowell, MA; and Seattle, WA. The State of California is home to not only the largest community of Cambodians outside Southeast Asia (Long Beach), but is also home to the most communities, including San Diego, greater Los Angeles County (including Long Beach and Orange County), Fresno, Stockton, and San Francisco.

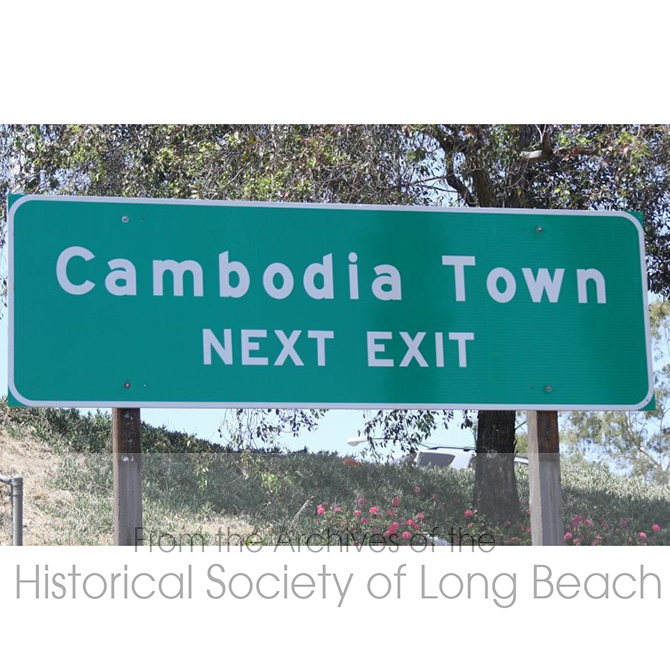

Long Beach, California

Images

Documents

✧ “Welcome to Cambodia Town,” The Press Telegram

✧ “Local Group Proposes Cambodia Town Designation,” Long Beach Business Journal

✧ “Almost Heaven Cambodia Town,” Khemara Times

✧ “Cambodia Town Proposal to Go Before City Council,” Long Beach Business Journal

Personal Accounts

Additional Resources

Lowell, Massachusetts

Images

Documents

✧ Cambodian American League of Lowell

✧ Lowell hopes to put ‘Little Cambodia’ on the Map, Boston.com

✧ Sokhary Chau bio page – City of Lowell

Additional Resources

✧ Welcome to Cambodia Town | A Celebration of Cambodian Culture in Lowell, Massachusetts, New England

Chicago, Illinois

Images

Additional Resources

✧ National Cambodian Heritage Museum and Killing Fields Memorial – Chicago, IL

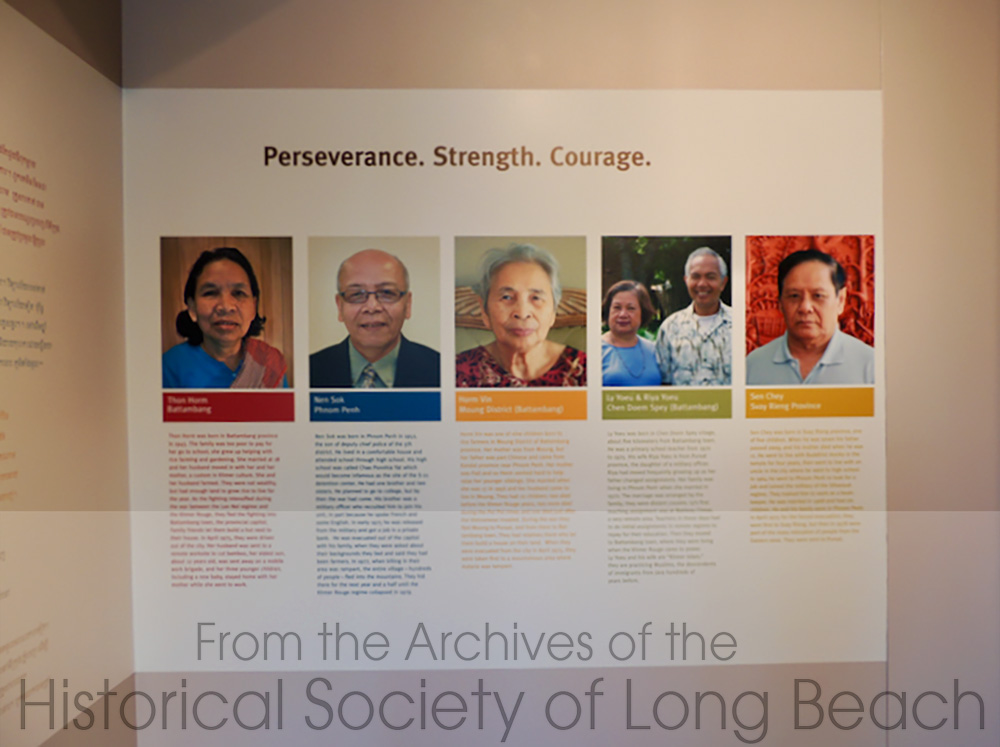

In 1989, Long Beach’s local paper, The Press-Telegram, published a six-part series titled Beyond the Killing Fields. The series focused on Cambodians in Long Beach, California, a city with the largest population of Cambodians outside of Southeast Asia. The themes and topics covered in the city resonate with broader experiences of Cambodians in the diaspora and the process of rebuilding lives and communities. The series appeared on the front page of the newspaper and was translated into Khmer, the Cambodian language, and provided to community members. In describing the series, the newspaper editors provided the following information.

Beyond the Killing Fields (1989) Press Telegram

Editor’s note: This year The Press-Telegram has focused on the 40,000 Cambodians who are trying to create new lives in Long Beach – from one man’s courageous return to his homeland to the excruciating trauma suffered by thousands who escaped genocide. In this six-part series we continue by showing the successes and disappointments of these newcomers in a rich picture of their lives in Long Beach today and their future beyond the killing fields.

Beyond the Killing Fields: Part 1

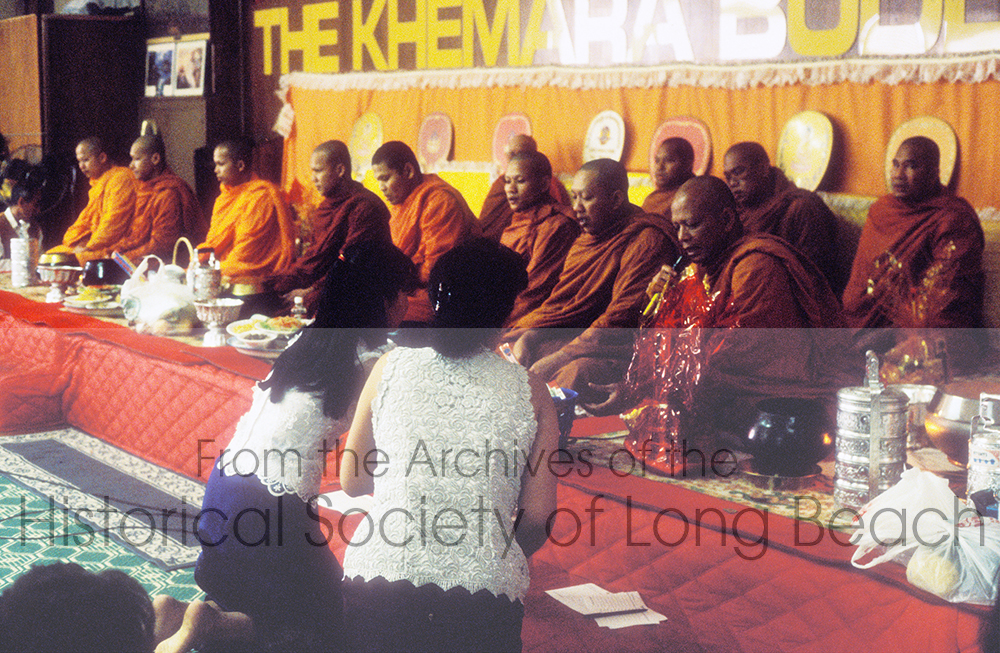

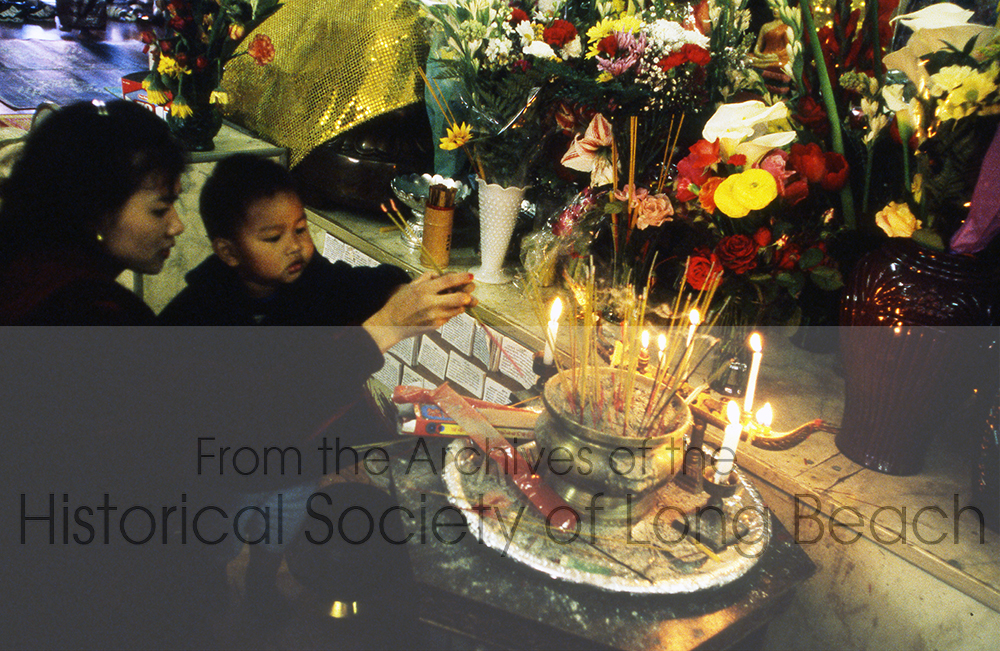

Topics: Educational challenges and success; Different challenges of Cambodians who came in 1975 versus those who came after 1979; Buddhist rituals, elders, the role of monks, and Buddhism in healing; Retaining cultural traditions, such as weddings; Conflict between the leaders running the two main Cambodian mutual assistance organizations in Long Beach

Documents

✧ Beyond the Killing Fields Part 1

Beyond the Killing Fields: Part 2

December 11, 1989: “Tenuous Grip on American Dream” and “Fading business strip saved by the influx of immigrants.” Susan Pack, staff writer, and Lynne Butterworth, photographer.

Topics: Restaurant owner and family story; Business development and contributions of Cambodian entrepreneurship; Cultural and social interaction through business ties and community relations

Documents

✧ Beyond the Killing Fields Part 2

Beyond the Killing Fields: Part 3

December 12, 1989: “Prejudice, fear greeted city’s newest ethnic group.” Susan Pack, staff writer, and Peggy Peattie, photographer.

Topics: racial barriers and conflicts in schools; ethnic and racial prejudice

Documents

✧ Beyond the Killing Fields Part 3

Beyond the Killing Fields: Part 4

December 13, 1989: “Many Cambodians break the bonds of poverty, stereotypes to own their own home.” Dorothy Korber Pack, staff writer, and Cristina Salvador, photographer.

Topics: overcoming stereotypes; housing trends in Cambodian community; economics

Documents

✧ Beyond the Killing Fields Part 4

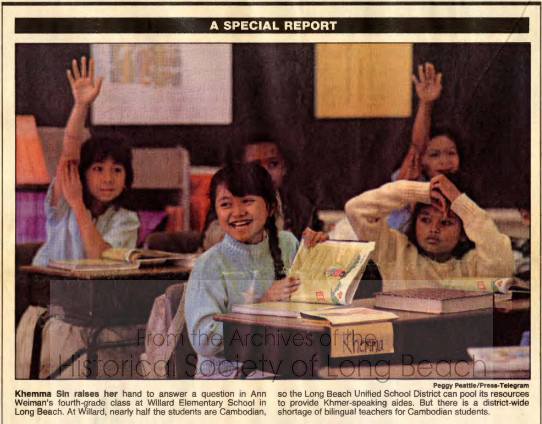

Beyond the Killing Fields: Part 5

December 14, 1989: “An influx of Cambodian students staggers LBUSD: Schools desperately need bilingual teachers.” Dorothy Korber, staff writer, and Peggy Peattie, photographer.

Topics: need for bilingual education and teachers; struggle of older generation to learn English; impact of racism on education and learning; opportunity for friendships forged in schools

Documents

✧ Beyond the Killing Fields Part 5

Beyond the Killing Fields: Part 6

December 15, 1989: “Leaving anguish behind, refugees look to the future: Cambodians guided by lesson in humanity.” Janet Wiscombe, staff writer, and Cristina Salvador, photographer.

Topics: survivors mass atrocity; comparative perspectives on the Holocaust and Cambodian genocide; becoming mainstream; erasing the pain

Documents

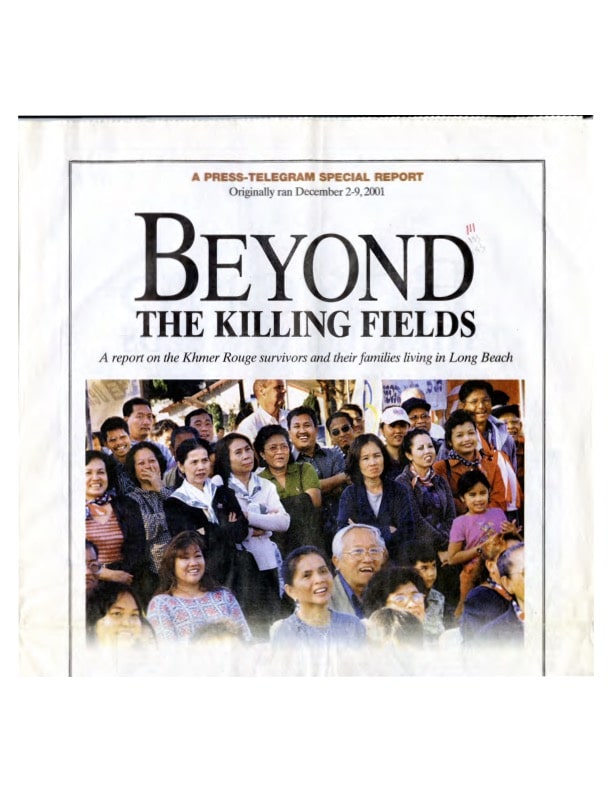

The Press-Telegram conducted a follow up to the Beyond the Killing Fields 1989 Special Report between December 2-9, 2001.

Beyond the Killing Fields (2001) Press-Telegram

Editor’s Note: In a four-year holocaust in the 1970s, the Khmer Rouge slaughtered nearly two million people in Cambodia. Their mass graves became known as the “killing fields.” Those who could escape the nightmare did. More than 145,000 Cambodian refugees fled to the United, hoping to share in the American dream. Many of them – more than 50,000 – settled in Long Beach, California, considered the largest Cambodian community outside Southeast Asia. Now, 20 years later, the horrors of war still haunt those who survived the killing fields. Some are succeeding, but many are not. But, amid this sense of hope and optimism, problems persist.

Many Cambodians in Long Beach feel isolated by culture, poverty, race and lack of education. Many do not speak English. Many distrusts authority. Many are suffering from severe mental disorders. Even raising children in the United States can be a struggle as families, the core of Cambodian traditions, suffer huge generation gaps. Parents complain that their American-born children have become too Americanized. However, there are plenty of success stories in the Cambodian community in Long Beach. Many of the killing fields survivors are looking to their children to achieve the American dream. Many of their businesses are thriving. Many barriers are being broken down.

In this special report, which ran as a series December 2-9, 2001, the Press-Telegram took an in-depth look at how Cambodians are coping in Long Beach. We reported on their struggles, their hopes and their dreams.

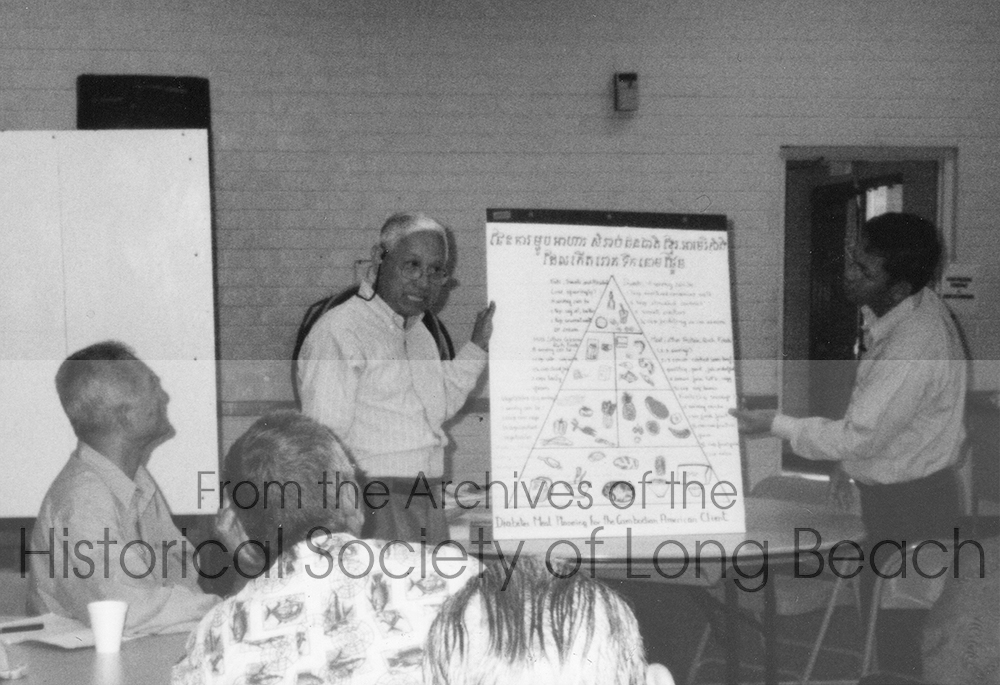

Topics: Mental and physical health; family ties; business; Buddhism; generational and language divide; praCh and rappers; Proposition 227 and bilingual education; crime and gangs; health and community outreach; traditional health practices; voting and local politics; homeland political involvement; community involvement and service.

Documents

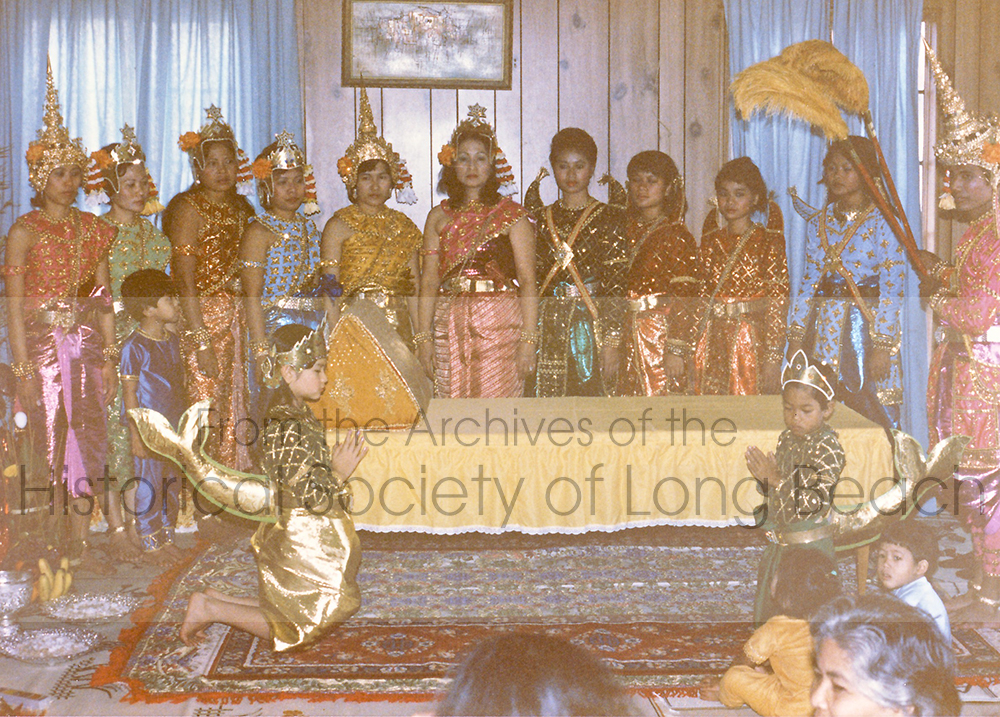

In the wake of tragedy and loss, many Cambodians found solace and purpose in reproducing cultural beliefs, values, practices, and traditions from one generation to the next. In this section, a sampling of the how continuity and preservation of Cambodian identity and heritage have been reproduced in a new context.

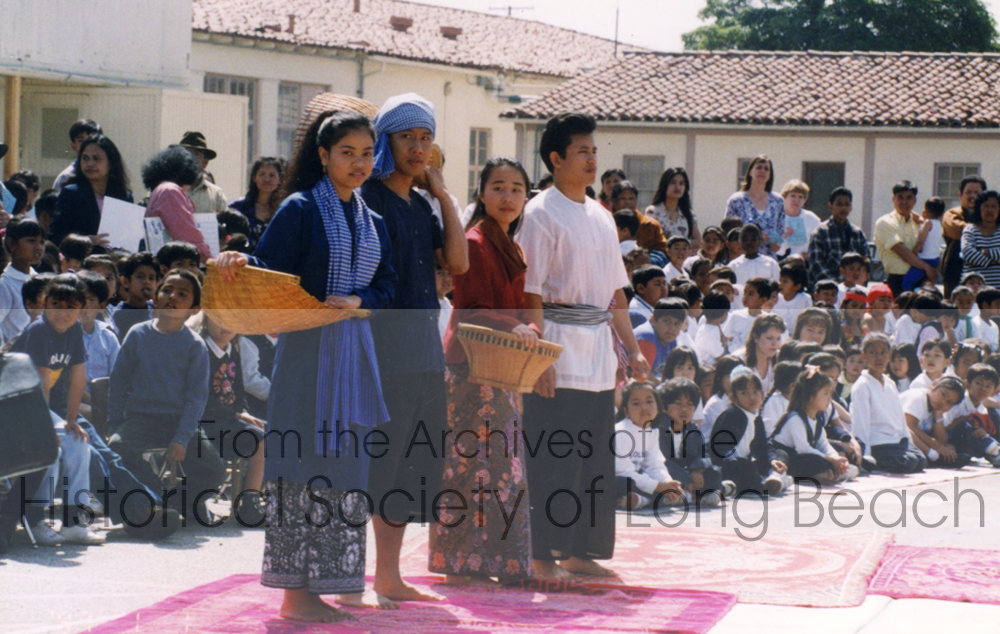

Dance, Music, and Costuming

Recreating Cambodian dance, music and costuming posed significant challenges to survivors. It is estimated that 90% of Cambodia’s artists had been killed by the Khmer Rouge. Only a few individuals possessed the knowledge and expertise to perform and train others. With limited resources and guidance, individuals had to rely on their memories to recreate the instruments, movements, lyrics, and intricate clothing.

Images

Documents

✧ Cambodian Dance Socialization

Videos

Additional Resources

✧ See Cambodian Profiles: Hang Leng and Sophiline Cheam Shapiro. There is also cultural information and images in the History and Culture page.

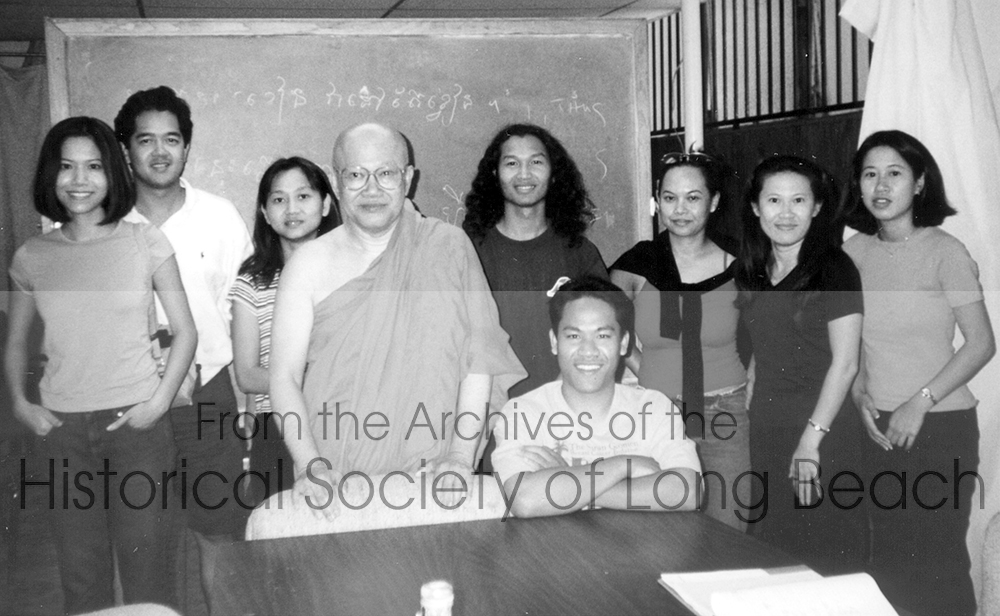

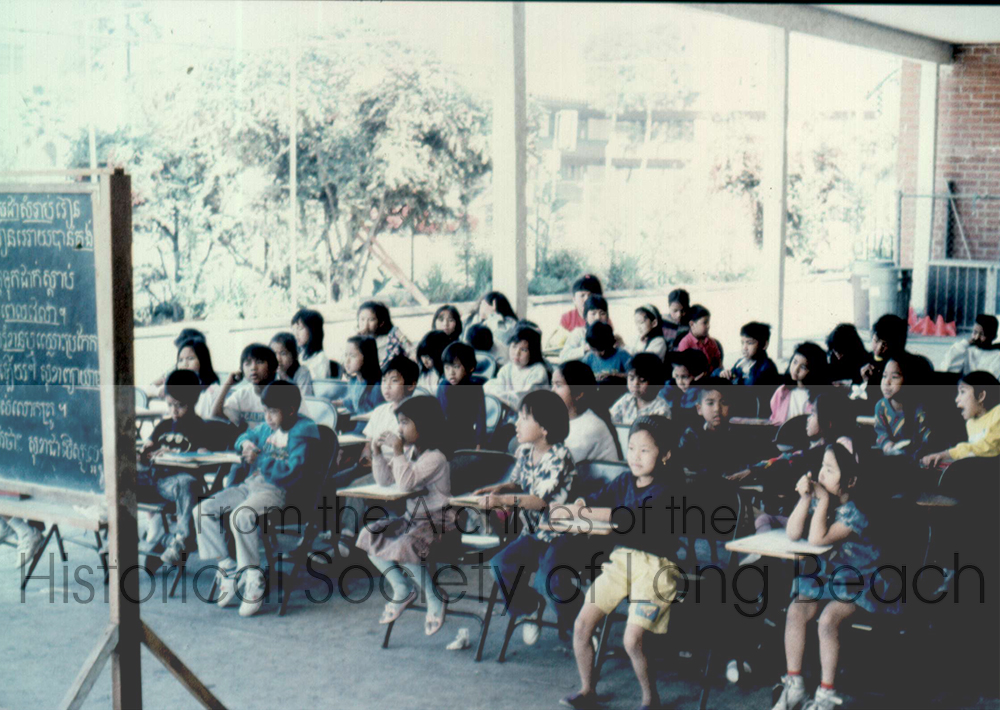

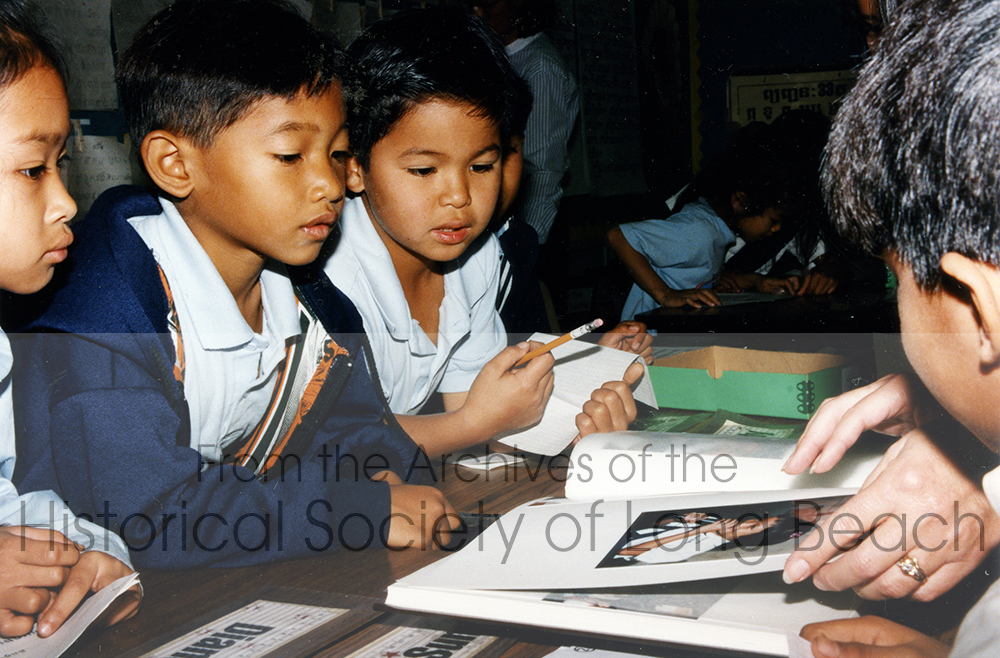

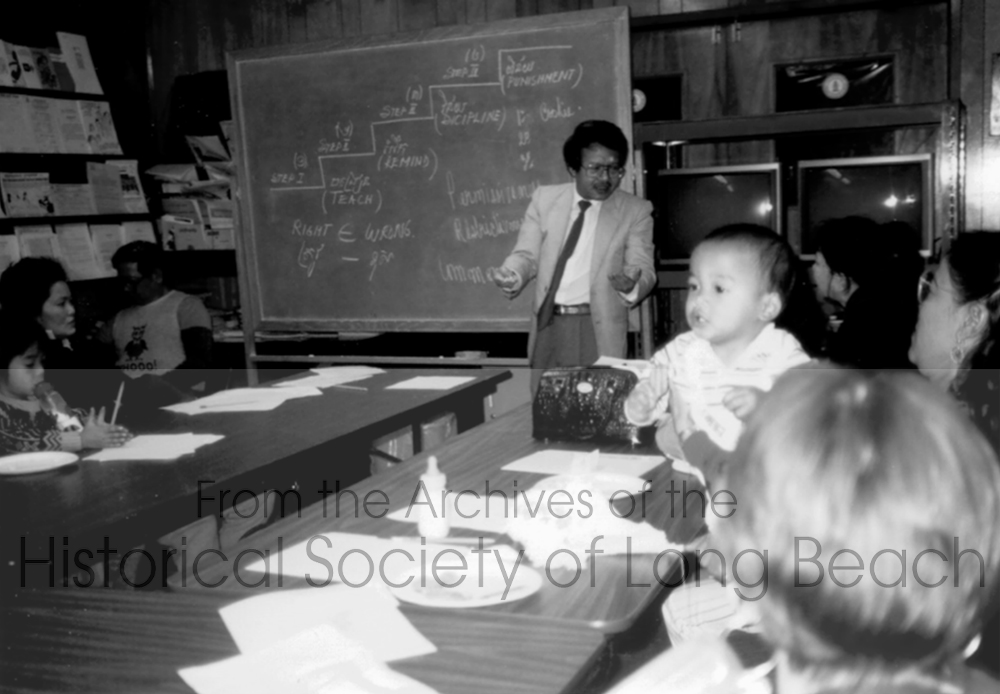

Public and Community Education in Khmer Language and Culture

Tremendous effort was invested in teaching Khmer (Cambodian language) to a new generation growing up in a new culture. School districts, Cambodian educators, Buddhist temples, and community organizations all offered language and culture programs that were supported from 1976 into the 2000s. Loss of funding and anti-bilingual propositions curtailed these efforts.

Images

Documents

✧ School District Example Khmer Language Lesson

✧ Introduction to Cambodian Culture

Personal Accounts

Additional Resources

✧ Whittier Elementary School Khmer (Bilingual) Program

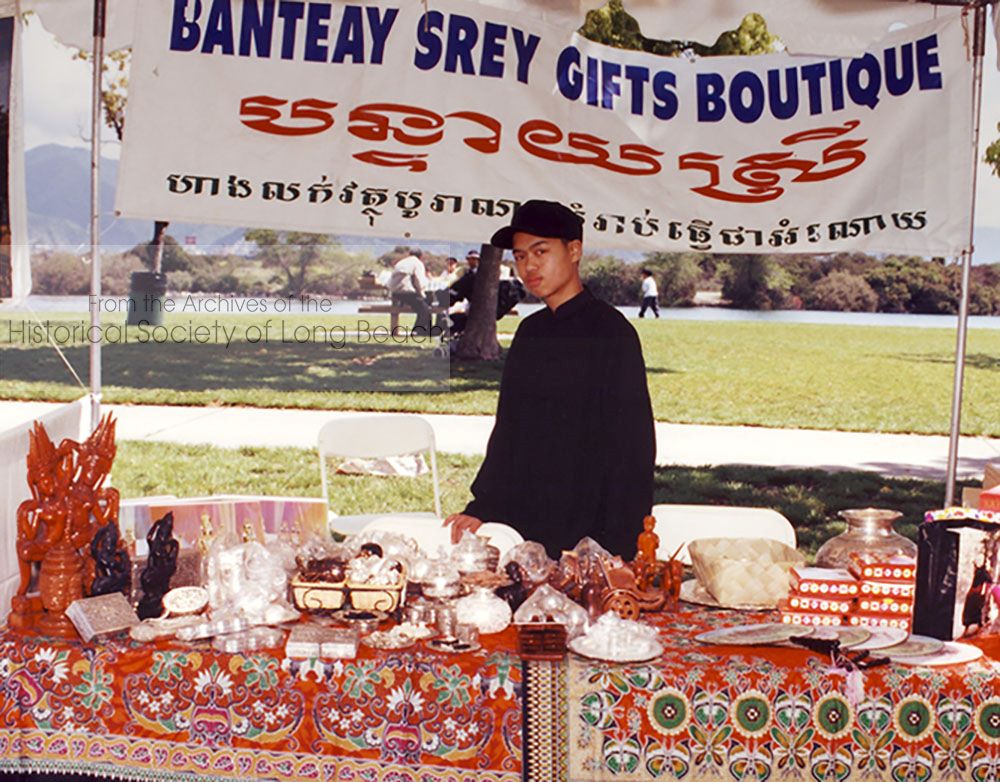

Community Festivals and Celebrations

Festivals and celebrations in Cambodian communities affirm the symbols and traditions of the culture. Community events are a way to celebrate Cambodian culture and to teach it to a new generation and to the broader society. It is also a time for Cambodian community organizations and individuals to participate in community building.

In Cambodian culture Choul Chnam Tmey, which means “entering the new year,” is celebrated traditionally over a three-day period beginning in mid-April. The Bayon Temple built by Jayavarman VII in the 12th century is traditionally thought of as a symbol of the New Year. In fact, it is called the “New Year temple” by some Cambodians. Over the years, the precise date of the New Year festivities in the Cambodian diaspora has been adjusted to accommodate work and school schedules, but this has not taken away from the significance of April as a time to focus on Cambodian public culture.

Images

Documents

✧ Overview of Cambodian New Year

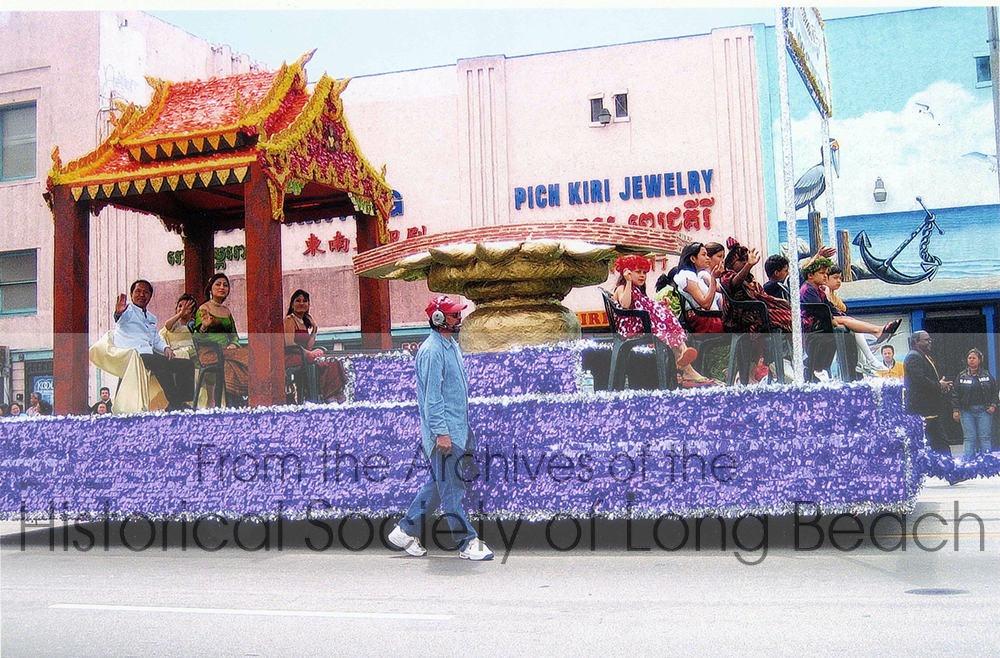

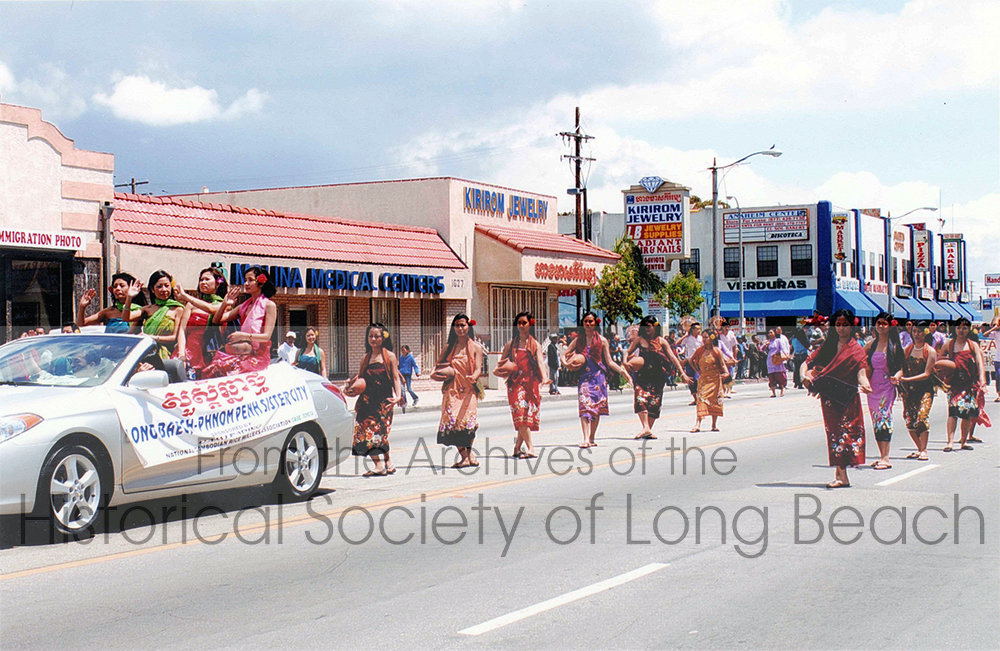

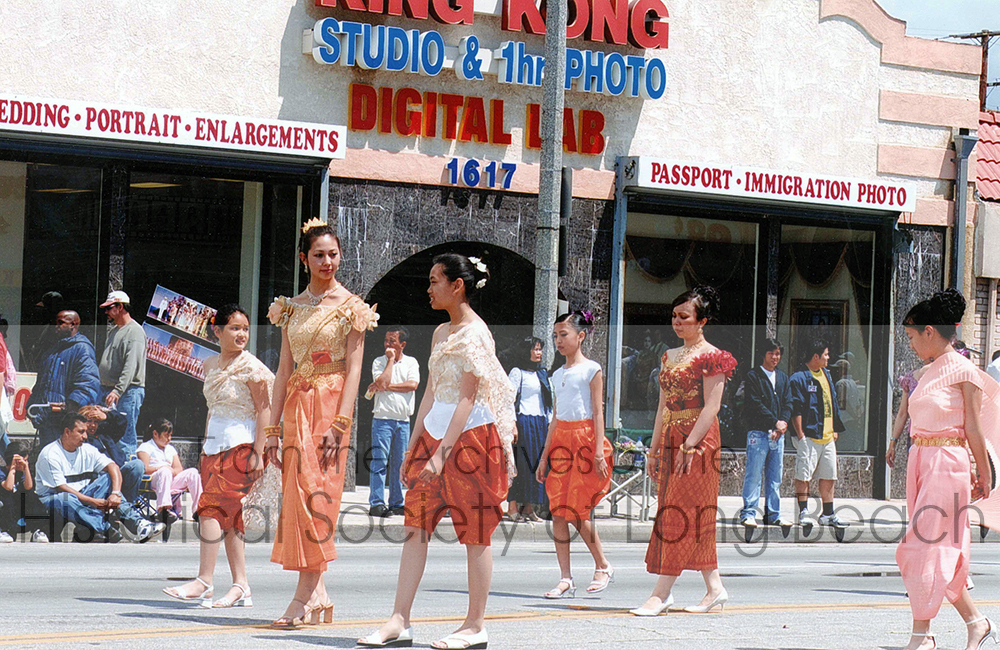

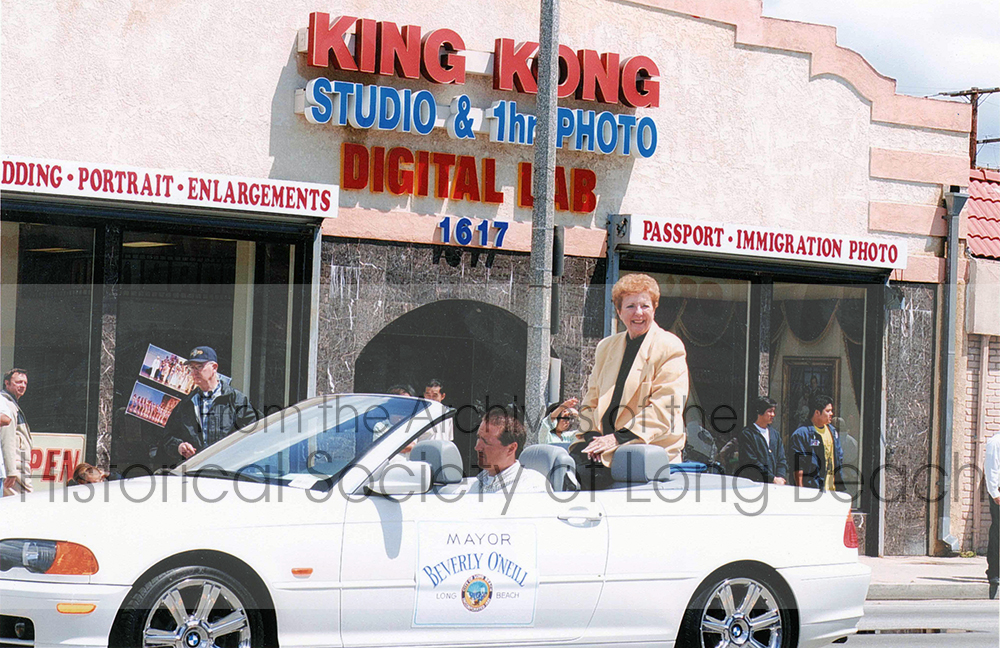

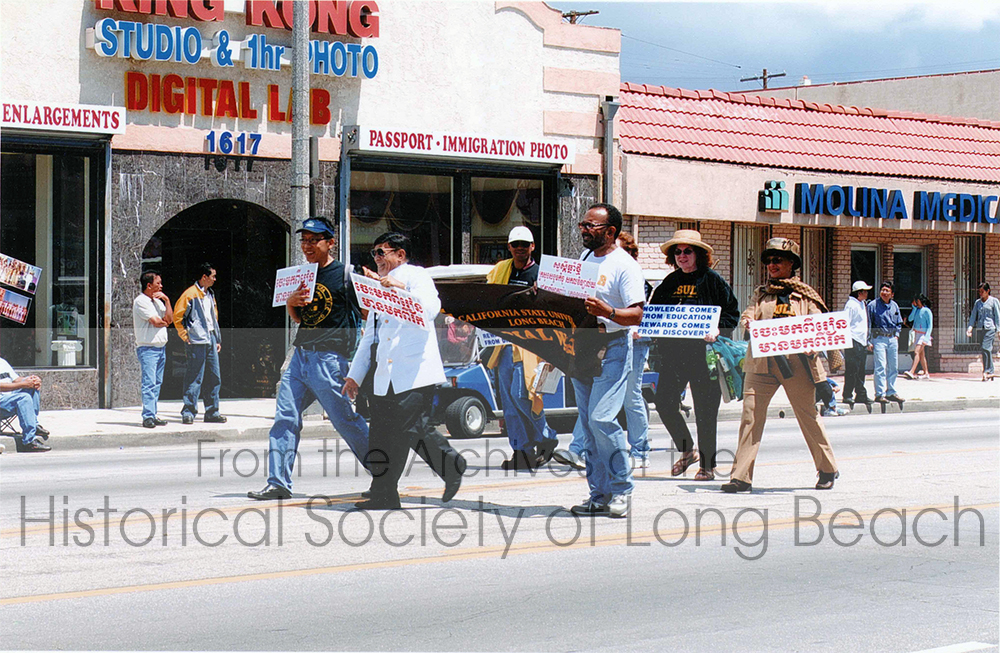

New Year Parade

A new tradition created in Long Beach, CA is the Cambodia Town New Year Parade. Its purpose is to promote Cambodian culture and businesses in the Cambodia Town area of Long Beach. The images in this section are from the first Cambodian New Year Parade, held on April 24, 2005, on Anaheim Street, Long Beach, CA.

Images

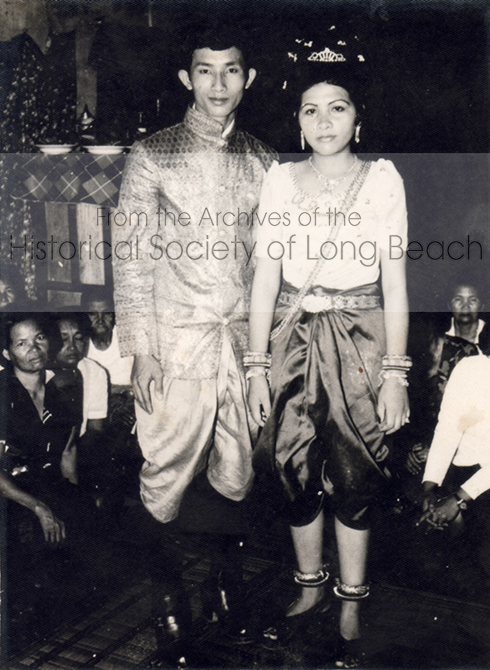

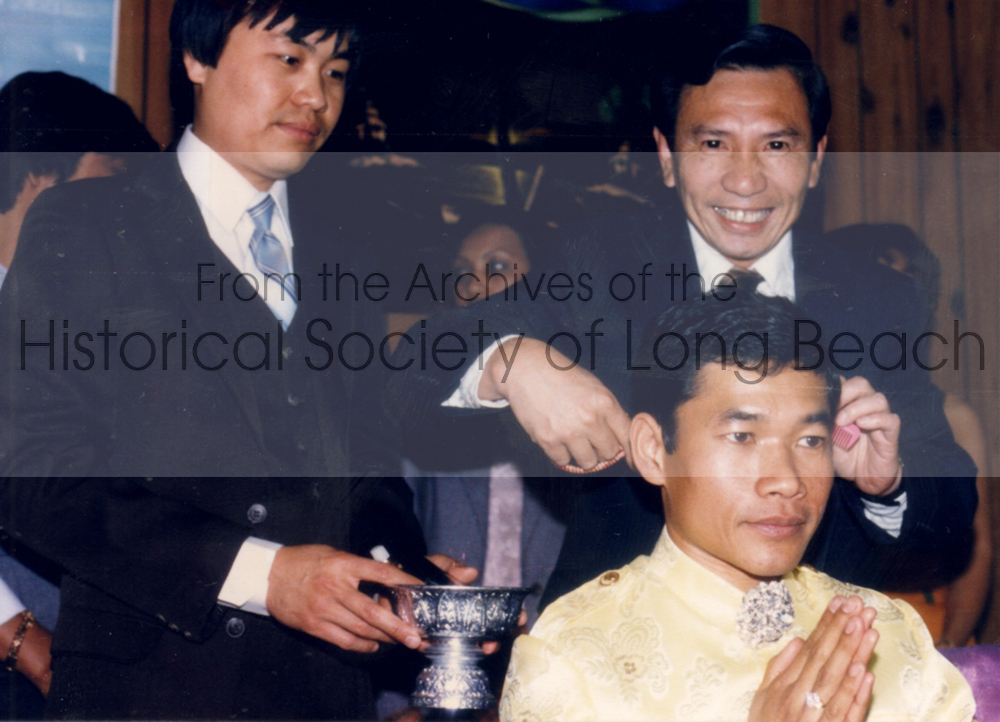

Weddings

Cambodian wedding traditions have adapted to the rhythm and flow of life in the United States and to new traditions created locally. This section describes the various parts of the wedding ceremony which not only creates a bond between husband and wife, but also binds the two families and community together.

Images

Documents

✧ Cambodian Traditional Marriage

✧ Description of Wedding Ceremonies

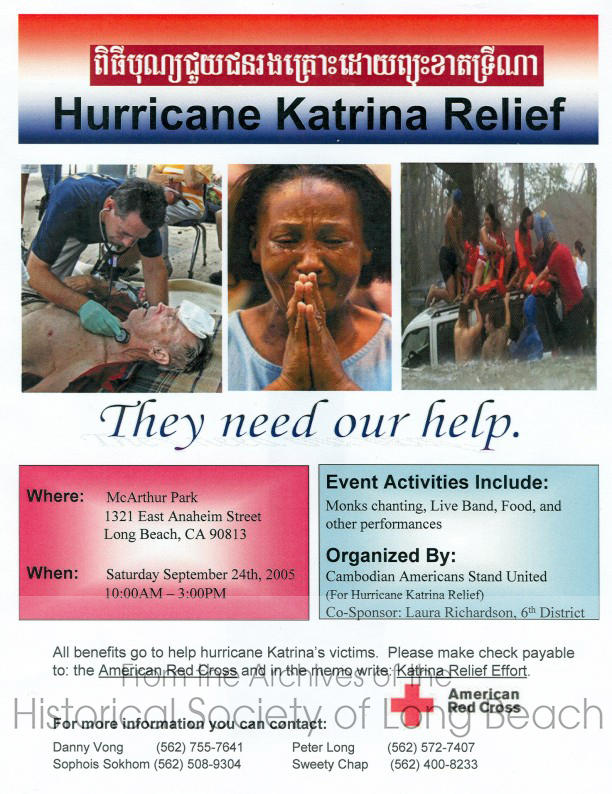

Ethnic organizations in the U.S. create services and make vital connections for newcomers, such as Cambodians. Cambodian community organizations, businesses and cultural groups have been the driving force behind continuing the traditions of their homeland and re-creating them in a new context for Cambodians and the broader public.

Images

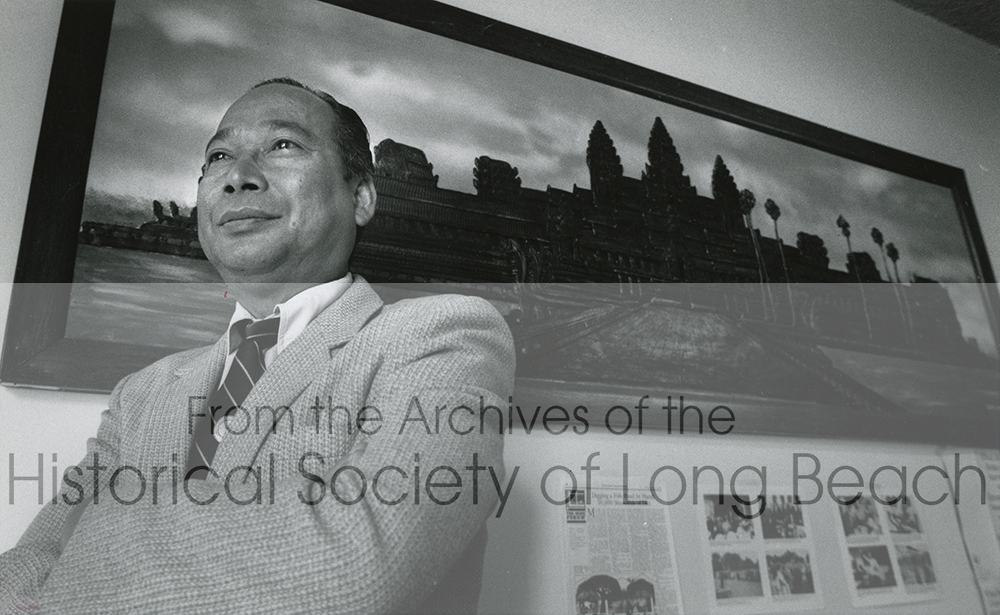

Political Office

Having just recently arrived as refugees, most Cambodians were absorbed by the events happening in Cambodia. Cambodians were particularly alarmed when the Vietnamese took control of the country. Even though the Vietnamese brought an end to the Khmer Rouge, their 10-year occupation of Cambodia made Cambodians afraid that Cambodia and Khmer culture would be absorbed by the Vietnamese and lost forever. Most all political efforts on the part of the Cambodians in the U.S. between 1976 and 1990 were focused on influencing national policy toward Cambodia and getting first the Khmer Rouge and then the Vietnamese to give up power.

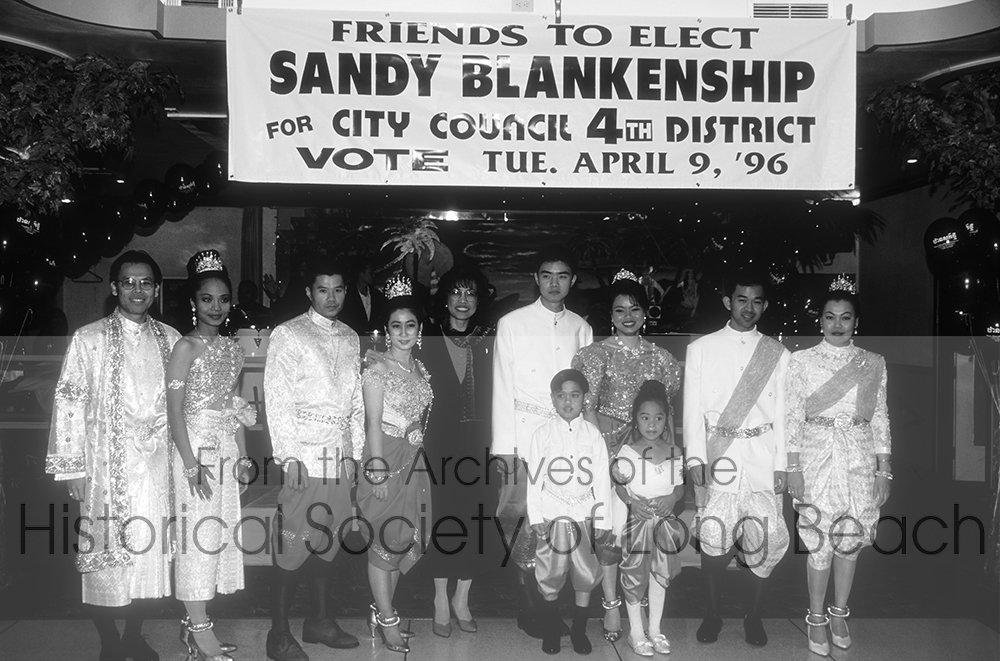

Mr. Nil Hul, of Long Beach, CA was among the first Cambodians to run for office at the local level. He was followed by Sandy Blankenship. Neither won their elections, but part of their goal in running was to lead the way for other Cambodians. Sokhary Chau, of Lowell, Massachusetts, was the first Cambodian American to be elected to a local office and the first Cambodian American mayor in the U.S. To learn more about Sokhary Chau, see Additional Resources below.

Images

Additional Resources

✧ First Cambodian American Mayor in the U.S.

✧ Sokhary Chau bio page – City of Lowell

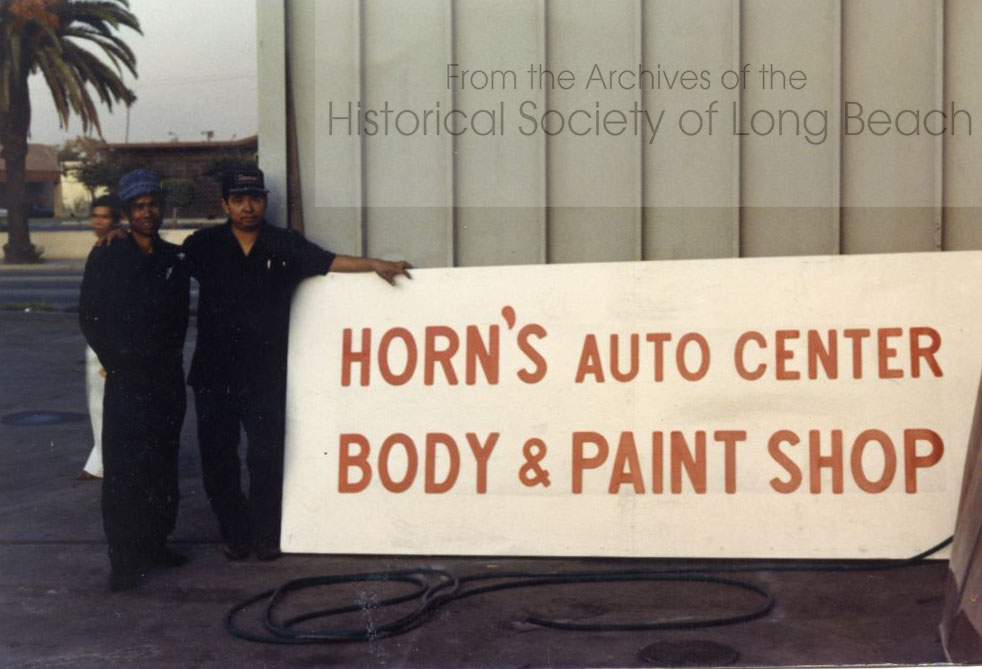

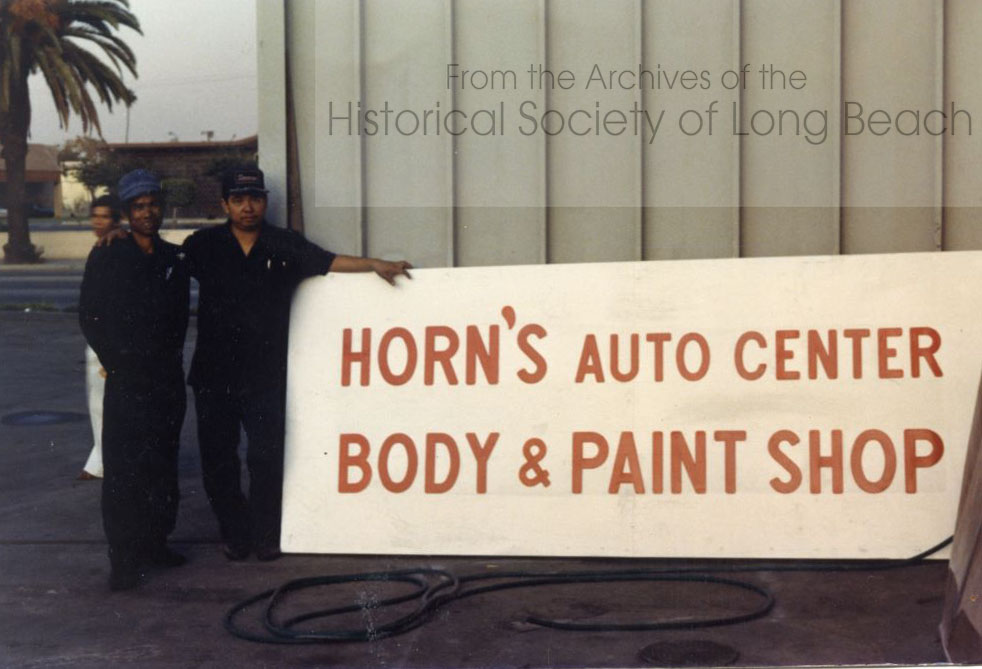

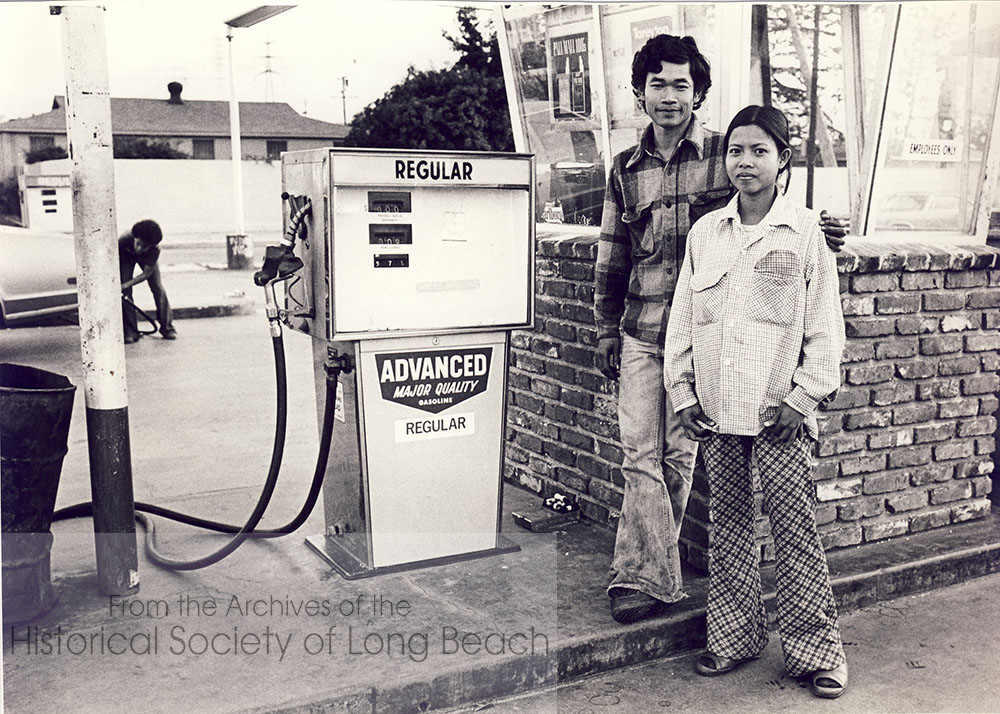

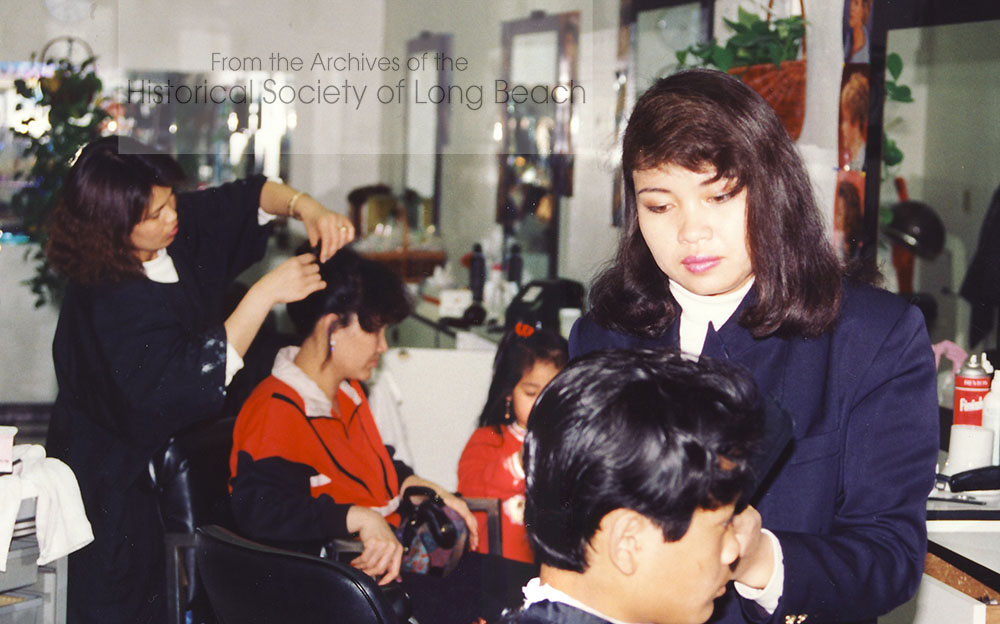

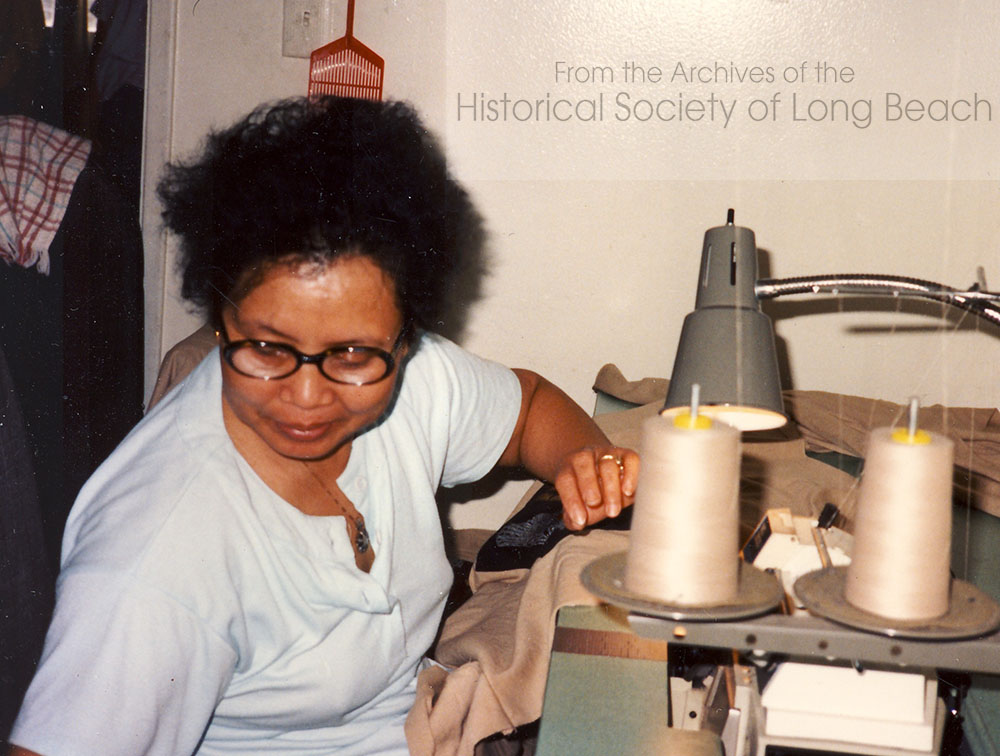

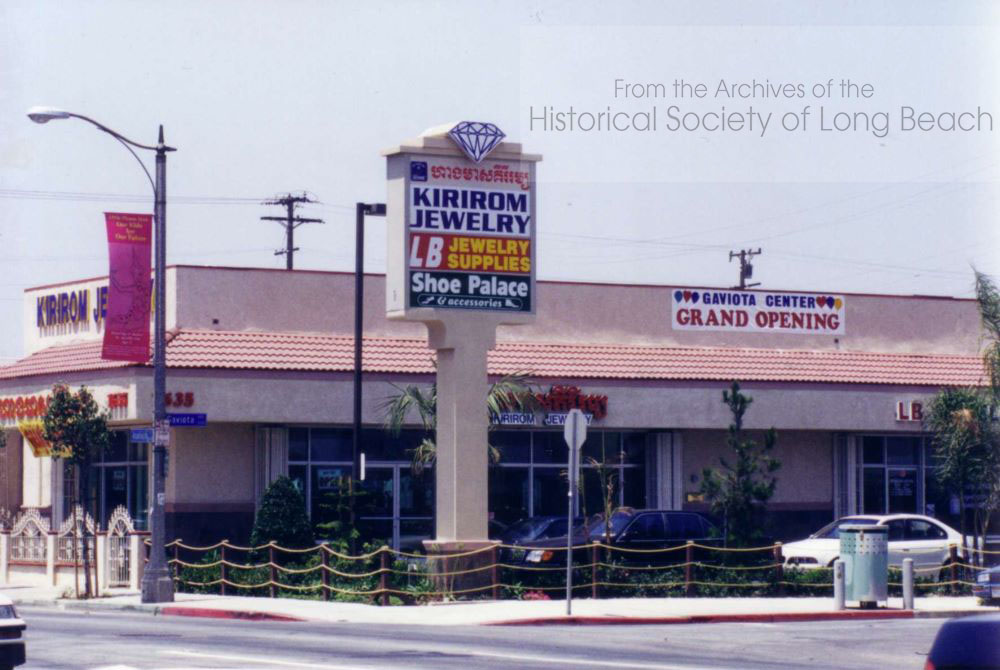

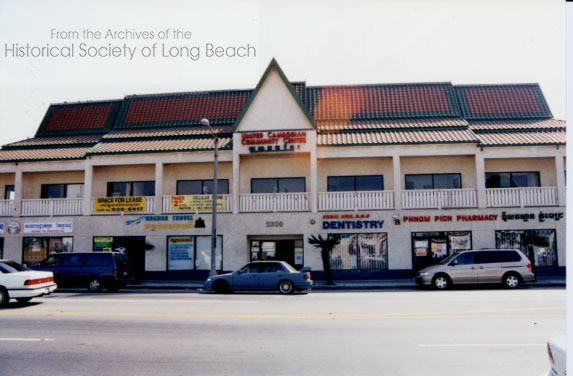

In 1975, when Cambodians began settling in the U.S., business development became an important way to serve other Cambodians and to become financially successful entrepreneurs. In cities in California, such as Long Beach, these businesses rejuvenated economically depressed areas. Businesses included auto repair, Cambodian groceries, restaurants, tailors, travel agents, jewelry stores, beauty salons, photo and video stores, and, of course, doughnut shops.

Images

Documents

✧ San Francisco Examiner: “Refugees Taste American Dream”

✧ The Los Angeles Reader: “Mrs. Noup’s Life Before Donuts”

Videos

Additional Resources

✧ Eater LA: “The Doughnut Kids are All Right”

✧ Medium: Death in Cambodia, Life in America: A Doughnut Kid’s Podcast About Her Father

Sports and other recreational activities are a way to build friendship and trust, and to develop physical skills and mental endurance. Through the efforts of individuals and community organizations, several sports groups and recreational opportunities have developed across the country. In most instances, these activities purposely attract other Cambodians. Some think this isolates Cambodians from mainstream society and illustrates a lack of integration. For a refugee population and a new generation growing up as Cambodian American, however, the camaraderie built through competitive sports and recreational activities has helped them build confidence and social networks that can be drawn upon as they advance in society.

For older Cambodians, recreational opportunities keep them healthy and tethered to others in the community. This section provides just a few examples.

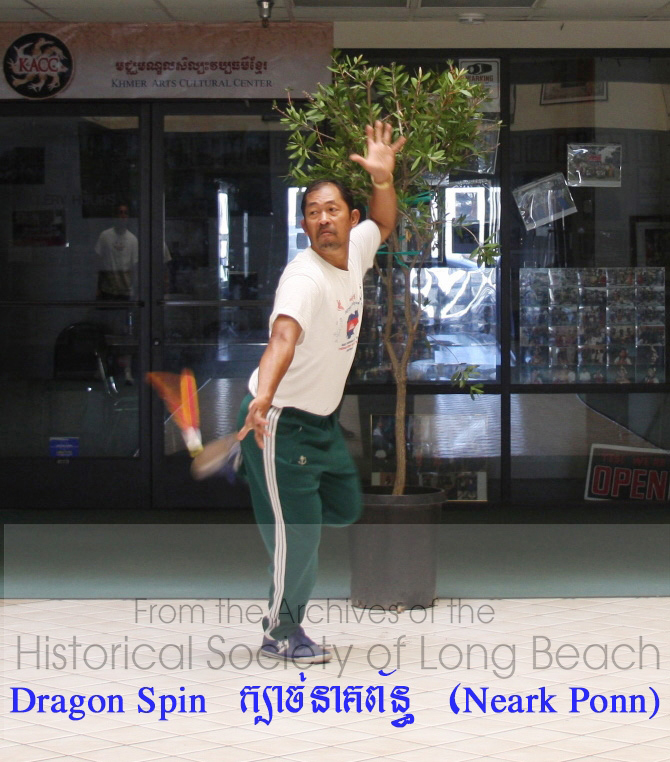

Sey (Cambodian Hacky Sak)

Sey is the Cambodian version of hacky sack played with a shuttlecock. Three or more players stand in a circle and kick the sey (shuttlecock) to each other in an attempt to keep it in the air for as long as possible. It is played using only one’s feet, knees, chest, or forearms – no hands. The game is played throughout Asia, but with regional variation in style and technique. In Cambodian sey, there are over 100 different moves; some mimic animals, some tell stories, and some are similar to the movements in Khmer dance. Individual style and creativity is also highly valued.

Images

Documents

✧ Sey

Videos

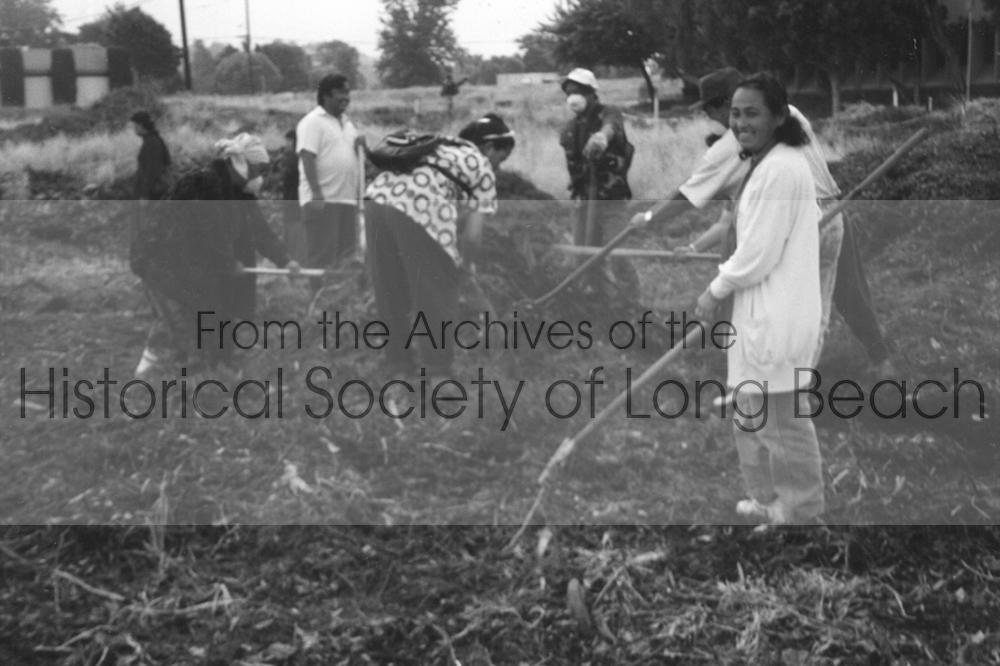

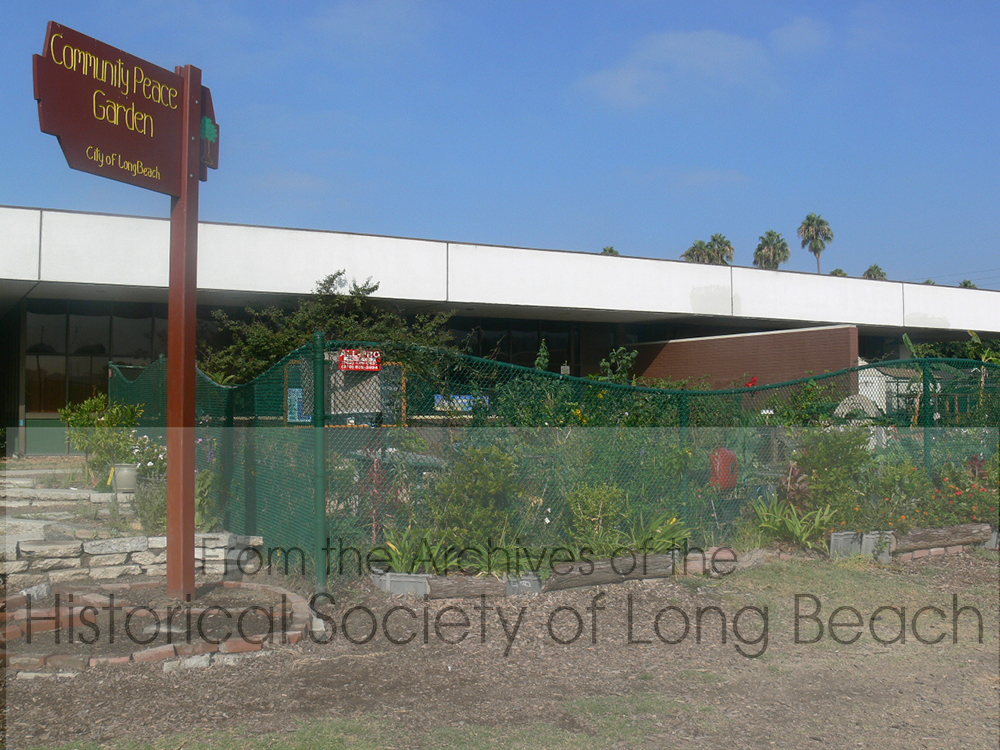

Gardening

Cambodian elders found adjustment to life in the U.S. particularly difficult after the trauma of the Khmer Rouge. Gardening is something the elders are expert in and requires no English language skills. It also provides opportunities to socialize with others who have experienced similar hardships.

Images

Documents

✧ Cambodian Seniors Nutrition Program, Gardening Guide

✧ Cambodian Seniors Garden Project

Videos

Additional Resources

✧ Refugees Rejoice in LB: Garden Plot Reminds Cambodians of Home

Bokator

Bokator (pronounced bokatau) is a form of Khmer kickboxing that has been taught in the U.S. See Oum Ry Ban in Cambodian Profiles for information on Pradal Serey (free boxing).

Images

Documents

✧ Bokator

Pradal Serey (Kickboxing)

Please refer to the section on Oum Ry Ban on the Cambodian Profiles page for more information about pradal serey.

Videos

Rock ‘n Roll had a profound effect on Cambodian pop music in the 1960s and 70s when Cambodian youth formed bands and performed for adoring crowds. Some of the Cambodians who had been in the U.S. or abroad when the country was closed by the Khmer Rouge had recordings of that music. Those recordings were copied and shared throughout the diaspora and became the background music for a new generation in exile (See the film, “Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten,” below). Inspired by this music, two American brothers formed the rock band, Dengue Fever, in 2001. They recruited Chhom Nimol who grew up in Cambodia as lead vocalist (See more information on Dengue Fever below).

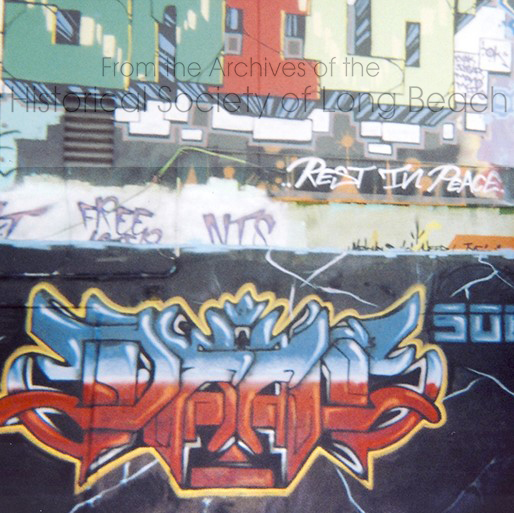

Meanwhile, Hip Hop and Rap were developing in the U.S. just as Cambodian refugees began arriving in large numbers. Many young Cambodians adopted the lifestyle and music of hip hop. PraCh Ly was at the forefront of this movement, telling the story of his life through rap combined with Cambodian classical instruments (See praCh Ly: Three Rap Lyrics and Cambodian Profiles). A copy of his first album found its way to Cambodia, was bootlegged, and by the time praCh visited the country of his birth as a young adult, he was surprised to find that he was well known.

Documents

✧ In the Shadow of Angkor: Three Rap Lyrics praCh Ly

Videos

Additional Resources

✧ NPR Music – Dengue Fever: Retro Pop, Cambodian Style

This section highlights cultural and social differences experienced by Cambodian Americans who were children when they arrived in the U.S. Most Cambodians faced difficulty adjusting to life in the U.S. The collection of 1.5 generation oral histories on this site provides insights into the unique issues Cambodian children faced in their personal and social lives as they adjusted to the new social environment. First, the entire family needed to learn English. Because young children learn languages relatively easily compared to adults, the burden of translating critical information often fell to the children of a family. Also, aspects of the culture, such as how to dress for school and what kind of food to bring for lunch, were unknown at first. Often families didn’t have much money, so they shopped at secondhand stores or wore what sponsors brought to them without knowing how items went together into an outfit. For example, Sophy Khut reports buying herself a nursing outfit to wear to school. To her it was a pretty white dress. Additionally, most Cambodian children were bullied at one time or another. Some report being beaten up and having to fight back to gain respect. Despite this, most of these children became productive and compassionate adults. Their experiences give us another way to see and think about our lives and culture in the U.S.

Cambodian refugees resettling in the United States confronted many challenges. Among them was a lack of English skills or knowledge of how the U.S. economic and political systems work. As for U.S. policy makers, they lacked knowledge of, and appreciation for, Cambodian family and work structures as well as appropriate approaches to physical and mental health care.

Mental Health

Among the more pressing concerns for local officials was how to treat the emotional needs of genocide survivors in ways that were culturally appropriate and effective. This was a theme touched upon by many of the oral history narrators. The materials below provides just a glimpse of the enormity of the distress.

Documents

✧ “Treating the Tormented” – Los Angeles Times – Jan. 4 1990

Personal Accounts

Additional Resources

Education

Another challenge was preparing school officials and educators at all levels for the influx of children and adults who would need English language instruction and help navigating U.S. culture. Some cities were fortunate to have highly educated Cambodians who could assist in developing programs and materials (see especially, Kry Lay, in Cambodian Profiles).

Documents

✧ Khmer Girls in Action 2011 Report

Personal Accounts

Additional Resources

✧ Pass or Fail in Cambodian Town

Facing and Overcoming Racism in Schools

Most Cambodian refugees wanted to work and do well in the U.S., but did not have the emotional stability, or language and/or work skills to find employment right away. They were forced to find housing in some of the worst areas of the cities where violent crimes occurred frequently. Additionally, refugee children were exposed to gangs in their neighborhoods and bullying and discrimination at school. For many Cambodians, it was like going from one “Killing Field” to another.

Life at home and in the outside society was so different, many children were uncertain how to fit in anywhere. To find some sense of belonging, some joined gangs and many of them either committed or were implicated in serious crimes for which they were then deported or threatened with deportation. Many of the Oral History narrators spoke about their experiences in school and with gangs and how they dealt with them. See especially Sithy Yi below and praCh Ly in Cambodian Profiles.

Documents

✧ “Beyond the Killing Fields,” a Press-Telegram Special Report 2001

Personal Accounts

Additional Resources

✧ Suggested Reading: Exiled: From the Killing Fields of Cambodia to California and Back – Katya Cengel (2023)